Posted: October 5th, 2016 | No Comments »

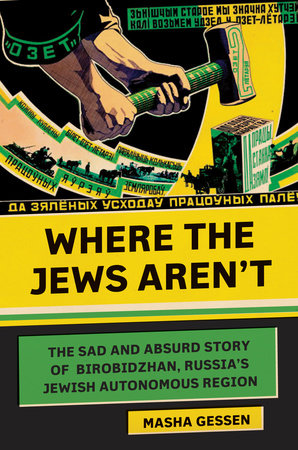

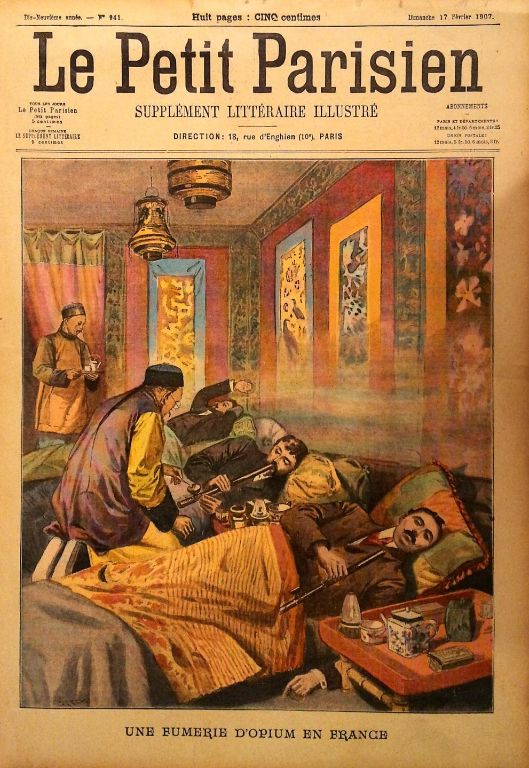

Masha Gessen’s new book Where the Jews Aren’t is about Birobidzhan, the USSR’s “homeland” for Jews. It was of course – thanks to climate, the better alternative of Palestine, Stalin’s purges and other factors, not exactly a roaring success and is nowadays mostly forgotten. And perhaps nothing to do with this blog you are thinking? Well, remember that Birodidzhan is close to the Chinese border (and on the Trans-Siberian Railway) and the Jews who went there cohabited the land with ethnic Koreans and both groups were plagued by marauding Chinese gangs known as the honghutzu, Red Beards – and everyone was cultivating opium as the local currency!!

The previously untold story of the Jews in twentieth-century Russia that reveals the complex, strange, and heart-wrenching truth behind the familiar narrative that begins with pogroms and ends with emigration.

In 1929, the Soviet Union declared the area of Birobidzhan a homeland for Jews. It was championed by a group of intellectuals who envisioned a place of post-oppression Jewish culture, and by the early 1930s, tens of thousands of Jews had moved there from the shtetls. The state-building ended quickly, in the late 1930s, with arrests and purges of the Communist Party and cultural elite, but after the Second World War, the newly named “Jewish Autonomous Region” received an influx of Jews dispossessed from what had once been the Pale, most of whom had lost families in the Holocaust. In the late 1940s, another wave of arrests swept through Birobidzhan, traumatizing the Jews into silence, and effectively making them invisible. Now Masha Gessen gives us a haunting account of the dream of Birobidzhan and how it became the cracked and crooked mirror in which we can see the true story of the Jews in twentieth-century Russia.

Posted: October 4th, 2016 | No Comments »

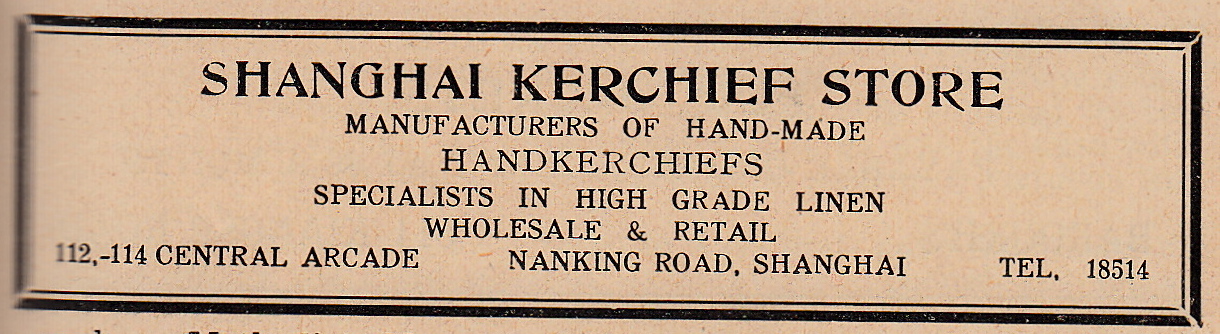

Now I’m a man who believes in a handkerchief rather than some scrappy old serviette or tissue. I also think a kerchief/head scarf a handy item for the ladies in case of typhoon winds or sudden plum rains – Grace Kelly probably did them with most style (below). So the Shanghai Kerchief Store, in the Central Arcade, just off the Nanking Road by the Cathay (Pace, if you must) Hotel was a useful place to pop into.

Posted: October 3rd, 2016 | No Comments »

Monday, 17th October 2016

7:00 pm – 9:00 pm

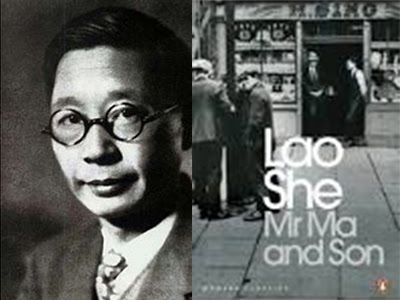

Mr. Ma and Son

Author: Lao She

Author: Lao She, 1929. English translation, William Dolby, 2013

Lao She (b.1899 – d.1966) was the pen name of Shu Qingchun, a noted Chinese novelist and dramatist of Manchu ethnicity. He was one of the most significant figures of 20th century Chinese literature and best known for his novel Rickshaw Boy and the play Teahouse.

From 1924 to 1929 he served as lecturer in the Chinese section of the (then) School of Oriental Studies (now the School of Oriental and African Studies) at the University of London teaching the Chinese Republic’s New National Language (Mandarin) to classes comprised of green horn missionaries, uninterested housewives, and all too often rowdy young men from London’s banks and business offices (including a young and China-obsessed Graham Greene.)

During this time Fiction Monthly (Xiaoshuo Yuebao) one of China’s most prestigious modern magazines serialized two of his novels: Old Chang’s Philosophy (1926) and Sir Chao Said (1927) that established him as a promising author in the new vernacular style or baihua. Writing the detailed evocations of his native Peking also served to an extent to assuage his homesickness.

Then while still in London he wrote something quite different, Mr. Ma and Son: Two Chinese in London (1929, serialized in Fiction Monthly). Mr. Ma and his son, Ma Wei, run an antiques shop nestled in a quiet street by St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Far from their native Peking, they struggle to navigate the bustling pavements and myriad social conventions of 1920s English society.

In the novel Lao She shows what life is like for Chinese people in the capital city of the nation which, for many decades, has been an anathema to China. It is both an indictment of British imperialist ideology and a Chinese wake-up call. (Lao She in London, by Anne Witchard, RAS China in Shanghai Monograph Series/Hong Kong University Press, 2012.)

RSVP: bookevents@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

ENTRANCE: Members: RMB Non Members: RMB

VENUE: Garden Books; 325 Changle Lu near Shan’anxi South Road 上海市黄浦区ç»å…´è·¯25弄2å· Shanghai

Posted: October 3rd, 2016 | No Comments »

It’s Rosh Hashanah, Jewish New Year and a few things to consider – last week another building, supposedly protected, was bulldozed in the former Jewish ghetto of Shanghai where the built heritage is reduced bit by bit annually; the crackdown on those wishing to practise Judaism in Kaifeng remains firmly in place. So not much good news from China in this area I’m afraid…

But, here’s a picture of a Jewish refugee family in Shanghai during World War Two…I like tho think around New Year…..

Posted: October 2nd, 2016 | No Comments »

A treat for Londoners this Wednesday at Asia House in central London….

Since Xi Jinping’s ascension to power in 2012, the leader of China’s Communist Party has often spoken about the Chinese dream, in both speeches as well as books. At the core of Xi’s dream for China is a vision to solve the nation’s problems and thereby return the country to its former global dominance.

“Realising the great renewal of the Chinese nation is the greatest dream in modern history,†he writes in The Governance of China.

That is Xi’s dream, but what exactly are the dreams of the rest of the nation?

Asia House is pleased to welcome Alec Ash and Rob Schmitz, two writers with books recently published on China, who will discuss the topic. Through the people they have interviewed for their books, both authors offer fresh and detailed perspectives on China from the bottom up.

In Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along a Shanghai Road, Rob Schmitz follows a series of people who live on the same street as he does in Shanghai. They’re a mixed bag and through their tales, as well as through Schmitz’s own insights as a long-time journalist in China, a picture emerges of 21st century China.

The New York Times and The Economist both described the book as “poignantâ€, while The Guardian said that the “great virtue of these books is that they offer Chinese people a voice, something that is often lacking in news coverage.â€

Moving north to Beijing, the characters we meet in Alec Ash’s book Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China are equally varied, urging readers once again to resist generalisations, but they do all have two things in common: they’re all born between 1985 and 1990 and they have all been to university. Ash talks to them about their dreams and their realities. Like the characters in Schmitz’s book, their stories are at times sad, at times happy and at times funny. The reader is once again left armed with a lot more knowledge about China today.

Wish Lanterns was described by Prospect as “compelling and beautifully writtenâ€. Writing in the FT, Jonathan Fenby said it was “one of the best I have read about the individuals who make up a country that is all too often regarded as a monolith, but which abounds with diversity on multiple levels.â€

This event will be chaired by Jemimah Steinfeld, Literature Programme Manager at Asia House and author of the book Little Emperors and Material Girls: Sex and Youth in Modern China. A Q&A will follow and copies of both books will be available to buy at the event.

Rob Schmitz is American National Public Radio’s Shanghai Bureau Chief. Before this recent appointment, he was the China correspondent for American Public Media’s Marketplace. He first went to China in 1996 and has reported on a range of topics from trade and labour to politics and education.

Alec Ash is a writer and journalist in Beijing. His articles have appeared in The Economist, BBC, Prospect, Foreign Policy and elsewhere. He is a contributor to the book Chinese Characters and co-editor of the anthology While We’re Here. Now in his early 30s, he spent the bulk of his 20s living in China.

times, tickets and other details here

Posted: October 1st, 2016 | No Comments »

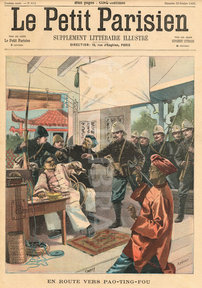

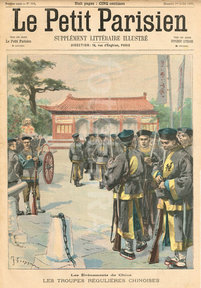

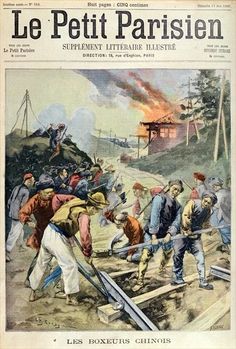

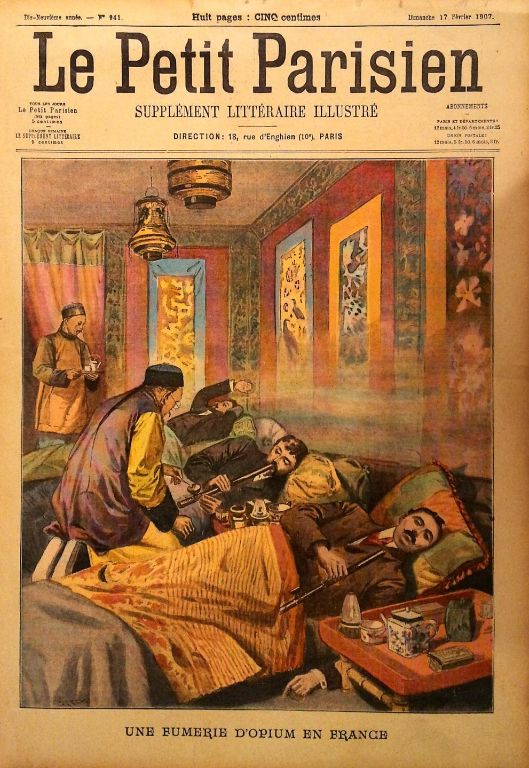

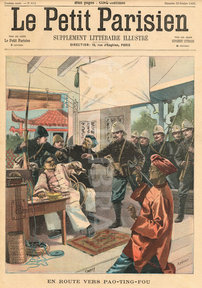

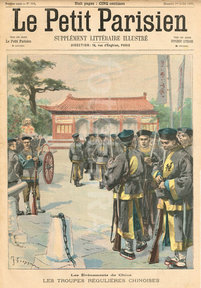

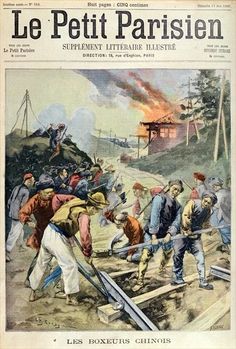

I blogged an 1898 issue of Le Petit Parisien the other week on the early warning calls of the Boxers in China. Petit Parisien quite often featured China or Chinese on its front covers…so here’s a selection….(not all that covered China by any means)….

Posted: September 30th, 2016 | No Comments »

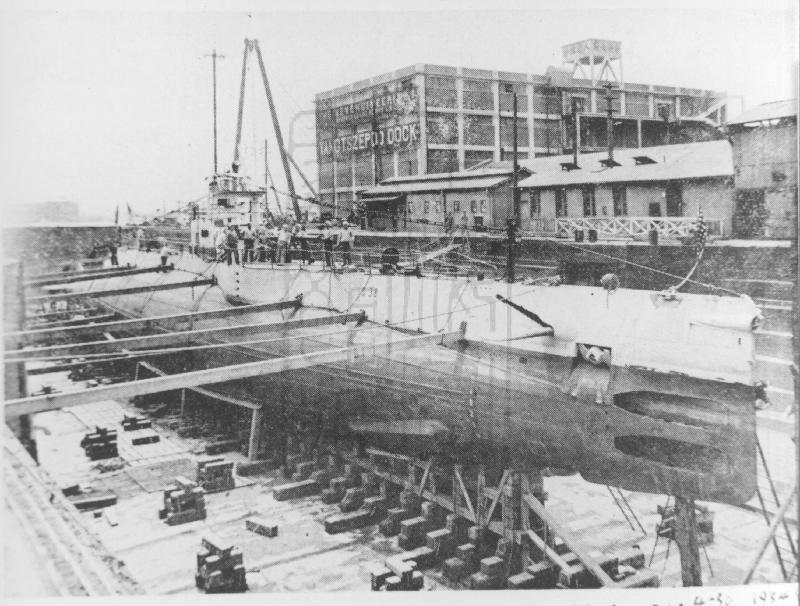

The development of the Huangpu riverside in Yangpu is one of the more intersting attempts at heritage in Shanghai that we’ve seen, I think (!). Of course it’s hard to tell from anything the Shanghai Daily says, plans change, the Party and developers lie and alter their intentions…but it appears interesting at least.

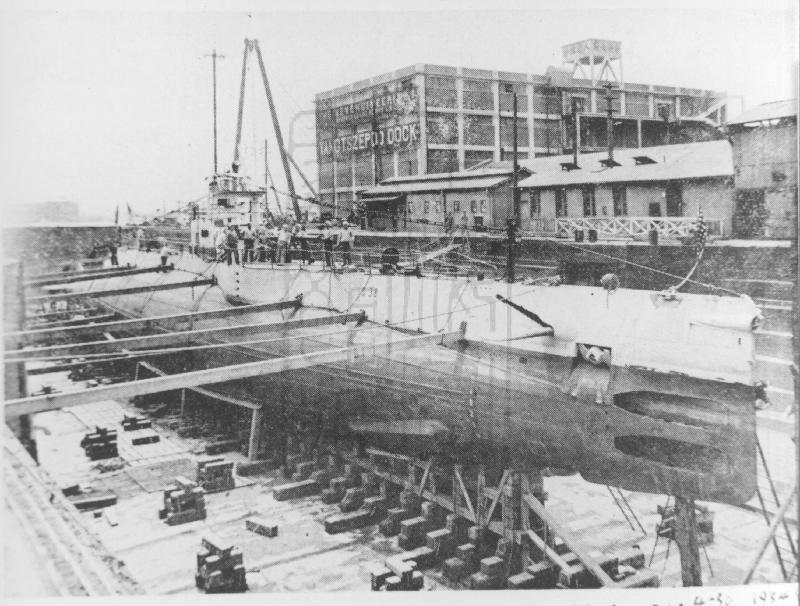

Positive is that the plan (as relayed to us from the state media of the Shanghai Daily in this article) does seem to take note of the district’s (the old Yangtszepoo or Y’Poo) industrial heritage as the powerhouse of Shanghai. They are acknowledging the paper mill, shipyard, water plant, textile mill, coal gas plant as well as the 1946 fish market. They claim that some industrial buildings will be renovated – though which ones remains unstated. An industrial heritage museum is planned (though personally I’d rather they just preserved the industrial heritage as opposed to destroying it and replacing it with a museum). Clearly it is not intended that all existing buildings will remain – in fact, one interpretation of the article could be that 60% of what remains (which is far from all that was there in 1949) will still go. Yangpu took a pounding in the run up to the EXPO in 2010 and road widening and “redevelopment” (i.e. destruction) has continued ever since. However, notions of industrial heritage in the district have always been extremely hazy and, this article at least, seems to indicate some greater clarity.

Here’s some of my previous blogs on Yangpu from the last eight years or so:

Shanghai’s Smokestacks

Mapping Yangpu

Yangpu Holds On…Just (mostly around Yulin Road)

The Massive Clearances on Pingliang Road

The Yangtszepoo Docks (1934)

Posted: September 29th, 2016 | No Comments »

A new self-published title, Mitya’s Harbin, minutely detailing Harbin White Russian life from after the Bolshevik revolution to the 1950s and the final community forced to leave communist China…..There’s been quite a swarm of self-published old China memoirs lately (it’s an age thing of course for the authors) and they all add something useful for researchers and historians. Lenore Zisserman’s book is no different and helps round out the Russian Harbin story (especially as it is currently being tinkered with by the local communist party up there to a) downplay that community’s differences with the USSR, b) ignore the compliance/collaboration of some in the community with the Japanese and c) make Harbin a second Hongkew and pretend it was a zone of safety for Jews in WW2 created by China)…

In the late 1950s, the Soviet Union was pressuring its citizens in Harbin, China, to return to Mother Russia. For the family of Dimitry (“Mitya”) Nikolayevich Zissermann and other White Russians, leaving their beloved “home town” had its perils. Few wanted to labor on the collective farms – their likely fate if they returned. But where else could they go, and how would they get there?

The Manchurian settlement of Harbin, headquarters of the Chinese Eastern Railway, had grown into a multicultural city by the early 1900s with an unmistakable Russian identity, coupled with unique Chinese-Russian relations. In the ensuing years, the city survived and sometimes even thrived during the Russian Revolution, Manchuria’s Japanese occupation, the Soviets’ expulsion of Japan from the region, Chinese civil war, and China’s Communist Revolution.

Harbin’s eventual transformation from an obscure rural settlement into a strategic Chinese manufacturing center exhibiting increasing animosity toward foreigners impacted the Russians in countless ways. This is one of their stories.