Hemingway and Gellhorn Do China HBO Style

Posted: July 7th, 2013 | 1 Comment »

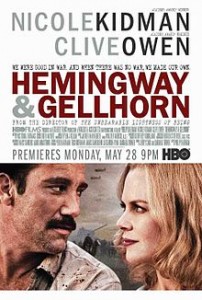

So I eventually got around to watching the HBO movie Hemingway and Gellhorn, despite a firm belief that all films about writers are doomed from the start as it’s basically a highly boring occupation. Why the hell do directors decide to make author bio-pics? Well, it’s basically all good fun. We spend a lot of time in Spain where John Dos Passos comes out of it particularly badly (although USA is a better book than any by Hemingway) and, for no good reason, Jose Robles becomes someone called Paco Zarra or something. To be honest Hemingway (the ever-good Clive Owen) I can personally take or leave, but I am a Martha Gellhorn fan, though Nicole Kidman rather accentuates a sexiness that may or may not have been so obvious in reality. We do at least see that she was the better and more serious correspondent.

We go to Florida for boozing and fishing, Madrid for fighting fascism and shagging, back to America and Cuba for more boozing and shagging before a quick detour to Finland before the ill-fated marriage. Kidman smoulders; Owen looks permanently sweaty. And then….China….

We do stick fairly close to the facts at the start – mention of Hemingway’s China missionary uncle, the wealth of prostitutes that flocked to Papa’s side in China (actually Hong Kong but they kind of truncated it all). Papa describes China as “filthy” which was actually more Gellhorn’s complaint on the trip. We seem to meet Chiang Kai-shek and Madame (nice cameo from Joan Chen) in Shanghai when the meet was in Chungking and there’s an odd moment where Gellhorn seems to witness the famous Newsreel Wong shot of the (posed?) lone crying baby at Shanghai Railway Station in the bomb debris – she didn’t (i did a whole post on that a while back). We get a Shanghai opium den, of course.

However, a few little interesting correct historical details so filter through – Chiang did take his false teeth out when he met them (apparently an honour). Madame translated. Gellhorn admitted she showed her ignorance of China in front of the couple and Madame snips at her rather nicely. The Chiang’s get a bashing, but then don’t they always these days as everybody either makes nice to Xinhua or (terrifyingly) actually believes the CCP view of history. The meeting with Zhou En-lai is more ludicrous – they met him in Chungking too and didn’t require an apparently endless voyage up the Yangtze. He was in his quite well appointed house, not in a cave; Gellhorn and Hemingway had no idea who he was; Gellhorn and Zhou spoke French, while in the film Zhou has a rather pronounced American accent and looks rather well fed; and then Zhou picks up his rifle to go fight the Japanese!! All very dramatic but wrong of course though Gellhorn, in her ignorance of most things China, was enamoured of Zhou.

Just as the Chiang’s are shown as venal and corrupt, Zhou is shown as a beacon of goodness and a reasonable individual – yea right, the man who sat by Mao’s side through the horrors of the post-1949 period was just a regular guy with a somewhat urbane attitude. A shame to see HBO feeding into this myth of Zhou that has been so carefully crafted and touted by Beijing. But then they’re not the first. Zhou fighting the Japs from his cave just after offering his insightful lit-crit on Hemingway’s work – it’s as if the ghost of Edgar Snow (like Hemingway, a man who’s horribly over-rated now while his far more talented wife is forgotten) had risen and walked in to write the script. Can’t see Xinhua complaining about this film! It then appears that the whole collapse of the Hemingway-Gellhorn marriage starts with Papa being jealous of Zhou!! Incodentally, no mention of Hemingway spying for Henry Morgenthau while in China.

That’s enough of that! I offer the section from my book Through the Looking Glass on the Hemingway-Gellhorn trip to China as my own view on the whole sojourn below…I’m sure plenty will disagree and that the pro-Zhou crowd will weigh in as well but anyway…

The Bell Tolls for China — Hemingway and Gellhorn

Chongqing was a magnet to some superstars and celebrities who, but for the war, would never have ventured there. Undoubtedly the biggest literary icon to arrive in Chongqing was Ernest Hemingway who came with his correspondent wife, the chain-smoking 32-year-old Martha Gellhorn. Later in the 1970s, aged nearly 70, she decided to write about the journeys she had taken in her long reporting career in her memoir Travels with Myself and Another. By far the funniest section of what is a very wry read was the story of her trip to the Far East with her “UC†— Unwilling Companion — a fitting nickname for the reluctant Hemingway. The American literary Titan and Gellhorn were only recently married and their trip to Asia was basically their typically untypical honeymoon and also marked the start of the end of their brief tempestuous marriage. The excited Gellhorn and the largely disinterested Hemingway quarrelled, fought, made up and laughed their way around the continent for three months during the war.

Their trip came about after Gellhorn was asked by Collier’s magazine, a weekly with a circulation of about three million, to go to China, Hong Kong, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies and Burma to cover the Chinese front, the state of British forces in the Far East and the scale of the Japanese threat, and to take a trip up the Burma Road, Chongqing’s vital supply line. This was a popular route for intrepid journalists at the time; as well as Carl Crow, Ian Morrison (G. E. Morrison’s son) traversed the infamous road while the intrepid woman journalist Alice L. B. Moats had also driven the entire length of the road as far as Chongqing for Collier’s already. Gellhorn had never been to Asia, but she wanted desperately to cover the war. She was an ardent supporter of American aid for China and was also keen to remain financially independent and not just sink into being Hemingway’s wife, chief groupie and camp-follower as she could so easily have done. Hemingway for his part was decidedly cool about the idea of traipsing around China, despite the fact that his favourite uncle had been a medical missionary in Shaanxi and had been awarded a medal by Sun Yat-sen. However, he eventually relented under Gellhorn’s insistence and was himself commissioned by the New York tabloid PM — a short-lived, advertising-free magazine founded by the crusading liberal Ralph Ingersoll — to report on the war in Asia with an accent on how the newly passed Lend- Lease Act was helping the Allies to win the war.

Though he had previously professed a desire to emulate Jack London and roam around the Far East, Hemingway was tempted to stay at home, or at least in Havana, and enjoy life a little with his recently cashed cheque for the then phenomenal sum of US$100,000 for the movie rights to For Whom the Bell Tolls. He was suddenly wealthy and respected and didn’t really need to rough it around Asia. Hemingway, 41 at the time of the trip, moaned incessantly from the start and suffered from his usual high-highs and low-lows, being what would now probably be diagnosed as bipolar. Their voyage was dismal: onboard service was non-existent under austere wartime conditions and they were pitched about in rough seas for most of the trip. A seasick Hemingway struggled ashore in Honolulu where, to his annoyance, he was smothered in garlands and mobbed by the locals, which led the combative novelist to declare to Gellhorn: “The next son of a bitch who touches me I am going to cool himâ€. The trip had not started well.

The pair reached Hong Kong where life improved dramatically. Gellhorn recalled Somerset Maugham-type visions of colonial life in the Orient and Hemingway, whose arrival had been anticipated eagerly in the pages of the South China Morning Post, was happy to find a ready circle of hangers-on to praise his books and pour his drinks in his base at the Hong Kong Hotel’s bar. They were able to enjoy the last, and distinctly hedonistic, days of Hong Kong before the Japanese invasion. Gellhorn filed some colourful pieces, hiring the well-known photographers Norman Soong and Newsreel Wong to shoot the accompanying pictures. However, duty beckoned and in March 1941 she flew to Chongqing, at night and at high altitude to avoid the Japanese planes. Hemingway decided to stay in Hong Kong, enjoying his new circle of admirers and hunting for pheasant. He was busy: Emily Hahn, who met Hemingway in Hong Kong claimed he introduced the concept of the Bloody Mary to the colony. Gellhorn departed with her notebook to take “the pulse of the nationâ€, while Hemingway predictably looked for yet more wildlife to kill, occasionally in the company of Morris “Two Gun†Cohen, Sun Yat-sen’s old Cockney bodyguard who was in semi-retirement in Hong Kong.

Gellhorn’s flight was rocky, with plenty of turbulence. When the plane’s air-speed dial froze, the pilot had to open the window to estimate the speed, knowing that if it fell below 63 miles per hour the plane would fall out of the sky. They made it to Kunming where Gellhorn reported from the Chinese end of the Burma Road and then headed back to Hong Kong where Hemingway was risking life and limb for PM’s readers by drinking, boxing and playing with firecrackers in their hotel room. She decided that Hemingway was just fine on his own and set off to explore Hong Kong and its crowds, brothels, dance halls, floods of Chinese refugees and squatters.

Eventually Hemingway could put off the trip to Chongqing no longer. Gellhorn, an obsessive on matters related to hygiene, stocked up on Keating’s Flea and Lice Powder and off they went. Hemingway was required to give rousing speeches to the troops at the frontline, a task he found not to his liking. However, as had been seen in the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway was a double- sided character, simultaneously deeply engaged in the cause while remaining the detached and cynical writer. Moving around on ponies did little to improve his mood as the great author’s feet grazed the ground when he was sitting on the back of the small but stout Mongolian steeds. When his pony got tired, Hemingway claims to have literally picked it up and carried it for a while, to Gellhorn’s great embarrassment. The inns they stayed in were full of bedbugs and broken plumbing which further exacerbated the mood of the great man. By this time Gellhorn too was starting to seriously tire of the vicissitudes of travel in war-torn China.

They eventually made it to Chongqing where Hemingway showed his compassionate side. Gellhorn noticed that the skin between her fingers was rotting and oozing puss, a condition known by the press corps as “China rotâ€. She had to apply a horrible smelling cream and wear gloves, which was not an easy process; and to compound her misery she contracted dysentery too. Hemingway’s response to his wife’s plight was: “Honest to God, M. You brought this on yourself. I told you not to washâ€. Gellhorn, the hygiene obsessive, was distraught and later recalled: “In 50 years of travel, China stands out in particular loo-going horrorâ€. 8 Hemingway, who was perfectly happy to go without a bath for a while, didn’t find much in Chongqing to like and Gellhorn was angry that the local Chungking Central Daily News pointed out that she was a bottle-blonde after the Hong Kong papers had praised her as a beauty — “For Whom the Belle Fallsâ€, as the Post’s “Birds Eye View†gossip column had put it. The pair were lucky as the Japanese didn’t bomb the city during their stay. They were shocked to meet Chiang Kai-shek without his dentures, which apparently was deemed a great honour, and Madame Chiang, who was dubbed by Hemingway “The Empress of Chinaâ€, a sobriquet that dogged her to her death and featured in several of her obituaries. They also met Zhou En-lai but neither American writer had any idea who this founding member of the Communist Party was or what to ask him, though apparently both were charmed by him (as were so many in the war-time press corps) and wrote to friends about how nice he seemed. At a point when she just wanted to escape the dirt, grime and skin infections of Chongqing, Gellhorn, who interviewed Zhou in French, wrote:

If he had said take my hand and I will lead you to the pleasure dome of Xanadu, I would have made sure that Xanadu wasn’t in China, asked for a minute to pick up my toothbrush and been ready to leave.Â

The couple left Chongqing for Rangoon where they parted and Hemingway returned to Hong Kong and his twin passions of hunting and drinking and perhaps, in a story he told repeatedly for years, enjoying an encounter with three Chinese prostitutes (at once). Hemingway enjoyed cocktails with Emily Hahn’s boyfriend Charles Boxer who said Hahn was suffering from stomach ulcers and couldn’t join the party, though she was of course secretly pregnant with Boxer’s child. Gellhorn found Rangoon “hotter than the inside of a steam boilerâ€, while Hemingway wrote to her that he was lost without her, proving that he was more romantic on the page than in person. Eventually both made it back to America. At home they walked into an argument with the editor of Collier’s who accused Hemingway of scooping Gellhorn with his PM articles. Hemingway, annoyed at the accusation, declared: “The only reason I went along was to look after Martha on a son of a bitching dangerous assignment in a shit filled countryâ€.10 China and Hemingway had not really hit it off. The argument fizzled out, with the editor opting not to get into any more serious debates about “shit filled countries†with the angry Hemingway. Gellhorn’s articles attracted a lot of attention, though she later admitted that she had been struck with wartime patriotism, glossed over the truth and didn’t reveal the corruption she had seen in the Generalissimo’s Chongqing. Hemingway too refrained from mentioning corruption to support the wartime Nationalist-Communist alliance. The superstars of Chongqing were as susceptible to the charms of Zhou En-lai, the cause of the Generalissimo and the dazzling nature of Madame Chiang as any new cub reporter.

What wasn’t known at the time was that Hemingway’s reporting was a secondary function of his trip. His primary task was to spy for US treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau. Perhaps it seems a little strange that the request for information came from the treasury rather than the president or the War Office but the shy, professorial and uncharismatic Morgenthau was, in his own quiet way, trying to mount a resistance to fascism while America was still technically neutral. Morgenthau, who was not always easy to please, was said to be delighted and impressed by Hemingway’s briefings; and all would have gone well, except that all the correspondence passed through the hands of Morgenthau’s right-hand man, Harry Dexter White, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy. Both Morgenthau (and by extension Roosevelt) and Stalin had all seen Hemingway’s briefings. It was also the beginning of the end of the Hemingway-Gellhorn marriage. When together on the trip they rowed and fought; and when they were apart they pined for each other. But the relationship was too combustible and later, in London during the later stages of the war, the marriage collapsed completely. All in all, the entire Hemingway-Gellhorn sojourn in China had been a mixed experience: both later professed their admiration and love for China and conversely their depression and hatred of the place. Hemingway perhaps summed up their journey best as an “unshakeable hangoverâ€.

With more than five major Hemingway biographies in print, including Michael Reynolds’s monumental work, Hemingway’s life is more than an open book to the world. Therefore it’s easy to dismiss any attempt to add to that life, let alone another book about Hemingway’s three-month trip to China with Martha Gellhorn in 1941. Yet, when I thumbed through Moreira’s book with its rich detail and copious references, both its depth and its style and tone drew my attention immediately. Moreira has obviously mined a significant chapter in Hemingway’s life that all previous biographers have failed to probe. Hemingway on the China Front is neither a trip report nor a honeymoon journal; Moreira has extended Hemingway’s biography significantly.