Posted: July 3rd, 2015 | No Comments »

I’m not sure how China’s current anti-smoking laws and campaigns are going…but they’ve had a go before, back in the 1930s….Shame Xi Jinping hasn’t revived the New Life Movement tagline….

Posted: July 2nd, 2015 | No Comments »

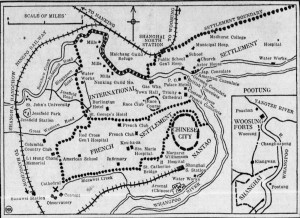

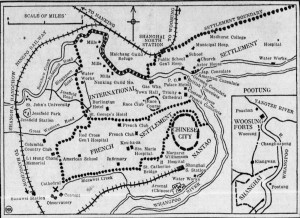

This map is from 1932 – not much else to say really!…..except that if you click on it then it should expand….

Posted: July 1st, 2015 | No Comments »

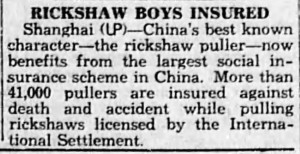

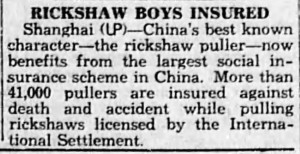

Lao She started writing his great novel Rickshaw Boy in the spring of 1936 and it appeared in the early months of 1937 in installments in magazines. It is a great description of the undoubtedly hard life of the ubiquitous rickshaw puller that was a feature of life in all Chinese cities at the time. Still, nowhere does Lao She mention that Camel Xiangzi might have had an insurance policy in his back pocket! Still, I think this insurance only applied in Shanghai’s International Settlement while poor Camel was trudging round the dusty hutongs of Peking at the time.

Posted: June 30th, 2015 | No Comments »

Dogs are definitely back in Shanghai after decades of being discouraged, banned and simply unaffordable…the last decade has seen a massive rise in dog ownership and, I guess, dog bite incidents. Any judge in the city now faced with a case regarding dog bites can, should they choose, revert to 1936 precedent and Shanghai treaty port law and invoke the ‘one bite’ precedent….

Posted: June 29th, 2015 | No Comments »

A quick plug for an event I’m moderating in London….ticket details and booking here….

Hyeonseo Lee was just seventeen when she fled North Korea. She found herself in China, alone and with no identity. Her mother’s first words over the telephone to her lost daughter were “Don’t come backâ€.

In her memoir The Girl with Seven Names, Lee recounts her life inside the secretive and brutal communist regime: the ‘self-criticism’ classes in primary school; forcibly joining the Youth Corps aged nine; and witnessing public executions of people who had not mourned enough for the death of Kim Il-Sung. She describes her escape and brave efforts to persuade her mother and brother to join her.

We are pleased to welcome Hyeonseo Lee to the Frontline Club to share her insight into growing up North Korea, the story of her escape and how she went on to rebuild her life and discover her identity. She will be talking to Paul French, an author and a widely published analyst and commentator on Asia, Asian politics and current affairs. He is author of North Korea: State of Paranoia and the international bestseller Midnight in Peking.

Hyeonseo Lee lived in North Korea until her escape in 1997. She arrived in Seoul in 2008, where she currently lives, and has recently graduated from Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. As a student, she was a Young Leader at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a journalist at the Ministry for Unification and a selected member of the ‘English for the Future’ programme at the British Embassy in Seoul. She is an international campaigner for North Korean human rights and refugee issues and speaks on the subject all over the world, including at the UN and the Oslo Freedom Forum.

PLEASE NOTE THIS EVENT WILL BE FILMED AND STREAMED LIVE ON OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

Posted: June 29th, 2015 | No Comments »

Franco David Magri’s Clash of Empire in South China examines the military operations that emerged from the Japanese invasion of Southern China…

Japan’s invasion of China in 1937 saw most major campaigns north of the Yangtze River, where Chinese industry was concentrated. The southern theater proved a more difficult challenge for Japan because of its enormous size, diverse terrain, and poor infrastructure, but Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek made a formidable stand that produced a veritable quagmire for a superior opponent–a stalemate much desired by the Allied nations. In the first book to cover this southern theater in detail, David Macri closely examines strategic decisions, campaigns, and operations and shows how they affected Allied grand strategy. Drawing on documents of U.S. and British officials, he reveals for the first time how the Sino-Japanese War served as a “proxy war” for the Allies: by keeping Japan’s military resources focused on southern China, they hoped to keep the enemy bogged down in a war of attrition that would prevent them from breaching British and Soviet territory. While the most immediate concern was preserving Siberia and its vast resources from invasion, Macri identifies Hong Kong as the keystone in that proxy war-vital in sustaining Chinese resistance against Japan as it provided the logistical interface between the outside world and battles in Hunan and Kwangtung provinces; a situation that emerged because of its vital rail connection to the city of Changsha. He describes the development of Anglo-Japanese low-intensity conflict at Hong Kong; he then explains the geopolitical significance of Hong Kong and southern China for the period following the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Opening a new window on this rarely studied theater, Macri underscores China’s symbolic importance for the Allies, depicting them as unequal partners who fought the Japanese for entirely different reasons-China for restoration of its national sovereignty, the Allies to keep the Japanese preoccupied. And by aiding China’s wartime efforts, the Allies further hoped to undermine Japanese propaganda designed to expel Western powers from its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. As Macri shows, Hong Kong was not just a sleepy British Colonial outpost on the fringes of the empire but an essential logistical component of the war, and to fully understand broader events Hong Kong must be viewed together with southern China as a single military zone. His account of that forgotten fight is a pioneering work that provides new insight into the origins of the Pacific War.

Posted: June 28th, 2015 | No Comments »

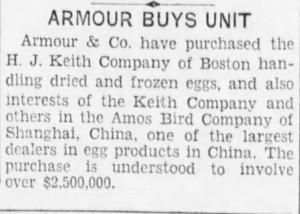

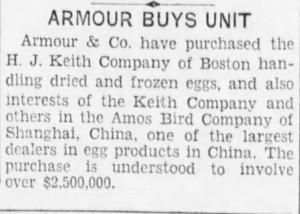

Despite repeated state media claims that Shanghai is intent on protecting its heritage it is reported that the former Amos Bird building on the Bund has been demolished. The structure on the North Bund was built in 1921 and was the egg packing and storage warehouse for the company. It was classified as an “immovable cultural relic” in 2011 but this does not appear to have made any difference once the developers decided they wanted it gone. Before 1949 the building was the largest refrigeration and storage site in the city. Amos Bird had operated on the site in one form or another since the First World War.

In the Chinese media the Amos Bird has been described as a “British Company” but I believe it was, in fact, an American company and was the Shanghai off-shoot of the HJ Keith dried egg company from Minneapolis, Minnesota but was registered and HQed in Boston. They sent a certain Morris Ovson, a Russian, to Shanghai in 1917 to establish a business producing dried and frozen eggs for export. He started the Amos Bird business in China. It was later incorporated into the Armour & Co. meat processing company of Chicago in 1929, as the newspaper article from August 1928 below shows.

Apologies but I don’t have a photo of the building in my records…if anyone does obviously I’d like to see some old shots of the building?

Posted: June 27th, 2015 | No Comments »

You’ve probably seen the movie with Anna May Wong, but have you read the book…the lovely cover of Arnold Bennett’s Piccadilly….