Posted: October 21st, 2015 | 5 Comments »

My thanks to Rob Baker, a great poster of old pictures of London, for this image of St Giles High Street in 1956. This part of the street no longer exists as it is now under the site of Centre Point by the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street’s eastern end. This end of St Giles High Street went and now probably many other similar streets that did survive in that area – Denmark Street, the old Tin Pan Alley, for instance – are also slated for partial or full demolition. This photo was taken by Allan Hailstone and is included in his book London: Portrait of a City.

Anyway our subject of interest is the L’Orient Restaurant. The sign indicates that it was an Indian restaurant though “L’Orient†is not a common name for an Indian restaurant. And so it seems L’Orient was somewhat more than an Indian restaurant. L’Orient was at No.56-59 St. Giles High Street (“Telephone: TEM 5717; Close to Tottenham Court Road tube; Open Daily for Lunches and Dinners”). The restaurant certainly did specialise in Indian food and claimed, in its adverts, to be “noted for curries and sweet dishesâ€. However, the restaurant also sold some Chinese and English dishes. Quite when they opened and finally closed I’m not sure. They were certainly open in 1947 when the restaurant made the New Statesman’s annual weekend review of restaurants.

The restaurant was also described as a “Linguists’ Rendezvous†in 1950 – i.e. a place where members of the Linguists’ Club went and met up. The Club, which was launched in 1932 and lasted until the early 1970s, acted as a meeting place and school for linguists, including interpreters, translators, language students, and other members who merely wanted to practice their language skills.

If anyone knows anything else – especially happens to have a menu? I’d love to hear.

Posted: October 20th, 2015 | No Comments »

Just out from Hong Kong’s excellent Blacksmith Books…..

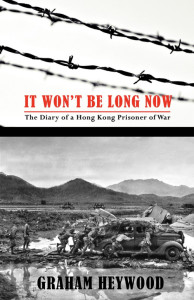

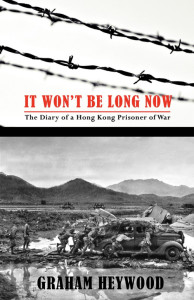

It Won’t Be Long Now: The Diary of a Hong Kong Prisoner of War

by Graham Heywood

Japan marched into Hong Kong at the outbreak of the Pacific War on December 8, 1941. On the same day, Graham Heywood was captured by the invading Japanese near the border while carrying out duties for the Royal Observatory. He was held at various places in the New Territories before being transported to the military Prisoner-of-War camp in Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. The Japanese refused to allow Heywood and his colleague Leonard Starbuck to join the civilians at the Stanley internment camp.

Heywood’s illustrated diary records his three-and-a-half years of internment, telling a story of hardship, adversity, and survival of malnutrition and disease; as well as repeated hopes of liberation and disappointment. As he awaits the end of the war, his reflections upon freedom and imprisonment bring realisations about life and how to live it.

“Accounts of life in the internment camp differed widely. One friend, an enthusiastic biologist, was full of his doings; he had grown champion vegetables, had seen all sort of rare birds (including vultures, after the corpses) and had run a successful yeast brewery. Altogether, he said, it had been a great experience … a bit too long, perhaps, but not bad fun at all. Another ended up her account by saying ‘Oh, Mr. Heywood, it was hell on earth’. It all depended on their point of view.â€

Heywood’s highly positive attitude to life is food for thought for all of us today, in the midst of increasing consumerism but decreasing spiritual satisfaction. We have enjoyed freedom and an abundance of material wealth in the 70 years since the end of the Pacific War, but we may not always recognise our true good fortune.

Posted: October 19th, 2015 | No Comments »

Please join the Royal Asiatic Society China, Beijing Branch, at the Bookworm for an Oct. 20 talk by Isabel Wolte on the adaptation of world literature classics in Chinese film.

WHEN: Tuesday, October 20th, 7:30-9:00 pm

WHERE: THE BOOKWORM, 4 Sanlitun Nanlu

HOW MUCH: RMB 75 for members of RASBJ or Bookworm, RMB 85 for non-members

RSVP: order@chinabookworm.com and write “Oct. 20 RASBJ talk†in the subject header. To pay online go to https://yoopay.cn/event/58538011

THIS EVENT IS CO-HOSTED BY THE BOOKWORM

Since the early 20th century, Chinese filmmakers have adapted masterpieces by world literary figures — from Guy de Maupassant to Oscar Wilde, from Nicholas Ostrovski to Gabriel Garcia Marquez — for their domestic audience. Foreign tales were appropriated, combined with Chinese cultural conventions and altered as deemed necessary for moral or political reasons. Dr. Isabel Wolte presents examples of this creativity, starting in the 1920’s. The talk will be moderated by long-time China correspondent Laura Daverio

MORE ABOUT THE SPEAKER:

Austrian scholar Dr. Isabel Wolte has been watching and studying Chinese cinema for more than three decades. She is Executive Director of her own company, China Film Consult and regularly teaches and publishes on Chinese cinema. She has worked as location manager and assistant director for several Austrian and German film productions in China. In addition to having been the first non-Chinese student at the Beijing Film Academy on World Literature in Chinese Cinema, where she obtained her PhD, Isabel also has a BSc in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence and an MSc in Ancient Philosophy (University of Edinburgh).

Posted: October 17th, 2015 | No Comments »

Alfred J. Rieber’s new study on Stalin and the Struggle for Supremacy in Eurasia contains some interesting comments on Xijiang and Manchuria as well as the nudging up of the USSR against Republican China and competition with Tokyo for influence in China…

This is a major new study of the successor states that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the great Russian, Habsburg, Iranian, Ottoman and Qing Empires and of the expansionist powers who renewed their struggle over the Eurasian borderlands through to the end of the Second World War. Surveying the great power rivalry between the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan for control over the Western and Far Eastern boundaries of Eurasia, Alfred J. Rieber provides a new framework for understanding the evolution of Soviet policy from the Revolution through to the beginning of the Cold War. Paying particular attention to the Soviet Union, the book charts how these powers adopted similar methods to the old ruling elites to expand and consolidate their conquests, ranging from colonisation and deportation to forced assimilation, but applied them with a force that far surpassed the practices of their imperial predecessors.

Posted: October 16th, 2015 | 29 Comments »

What do we know about the old Zeitgeist Bookshop in Shanghai? And why would we want to know more? Well, the Zeitgeist Bookshop was operating from at least the late 1920s from premises near Soochow (Suzhou) Creek on 130 North Soochow Road (now Suzhou Road North).Or maybe it was somewhere else – the American Communist journal New Masses lists the store at 130 North Soochow, but The People’s Tribune, published by the China United Press in 1933 gives the address as Bubbling Well Road. Of course, what I don’t have but would like is a photograph which would settle the matter?

The Zeigeist was run by a German woman (though Rewi Alley in his autobiography says she was Dutch – but he was 90 when he wrote that!), Fraulein Irene E.I. Wiedemeyer (or Wedemeyer, or sometimes Weitemeyer) and her younger sister. At some point Frau Wiedemeyer married Wu Shao-kuo, a Chinese communist party member she had met in Germany some time around 1925, but always retained her German name. At some point it appears Frau Wiedemeyer studied at the Sun Yat-sen University in Moscow around 1926-27. She was, according to the Shanghai Municipal Police, a member of the Noulens Defense Committee (a notorious comunist spy case) and the Society of Friends of the U. S. S. R. in Shanghai. As to what else we know about Wiedemeyer? she was a German Jew with, according to Ruth Price, a biographer of Agnes Smedley, “freckled skin, milk-blue eyes and unmanageable red hair.” (though how she knows this is not entirely clear as the source isn’t footnoted).

Why should we be interested? The Zeitgeist was generally regarded throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s as a “clearing house” for communist information. Frau Wiedemeyer had links to the Chinese communist movement as well as to the NKVD (later KGB) operating in the city during the decade through her close friendship with Mrs VN Sotov, the wife of the Head of the Russian News Agency TASS in Shanghai. As well as TASS/Comintern agents and Chinese communists, Hotsumi Ozaki, the Japanese informant in the Soviet spy ring connected to Richard Sorge frequented the shop. It was at the Zeitgeist that Ozaki met Agnes Smedley, the American communist. Sorge himself also made contact with Smedley at the Zeitgeist while Roger Hollis (later Mi5 director and suspected Soviet spy), American communist Harold Isaacs, the South African Trostskyist Frank Glass (who of course fell out with the Stalinists running the bookshop) and George Hatem (Ma Haide), the American doctor turned communist, also visited.

The Zeitgeist was in fact the Shanghai branch of the Zeitgeist Buchhandlung group of Berlin, a chain of shops that distributed pro-Soviet books and materials. Funding for the chain came from the coffers of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers in Moscow, a communist front organisation, and was arranged by the Comintern’s Willi Muenzenberg. The shop seems to have remained in operation until about 1933 or slightly long after which the Nazis in Germany cut off her contacts with the German Communist Party who supplied her with materials and books.

What did the bookshop look like? we only really have one or two descriptions and these are that it was about twelve by eighteen feet in size and poorly lit. Despite this rather small location the Zeitgeist did sell books in at least three languages (German, Chinese, Russian) and have the occasional art exhibition – for instance, an exhibition of new German graphic art in 1932.

Frau Weidemeyer was not to be put off. She visited Europe in late 1933 and returned to Shanghai in September 1934 to open a new bookshop in a new location, 410 Szechuan Road, this time as the Shanghai representative of the International Publishers company, an affiliate of the American Communist Party.

Posted: October 15th, 2015 | No Comments »

I recently came across Tong Lam’s 2011 book A Passion for Facts: Social Surveys and the Construction of the Chinese Nation-State, 1900–1949. It’s a good read and one thing that struck me was the section on that old stat that’s always repeated ad nauseum – China’s population of 400 million in the 1930s. It’s perhaps best remembered now as a stat from the continued interest and frequent re-publishings of Carl Crow’s Four Hundred Million Customers (1937) as well as the Joris Ivan’s pro-Chinese documentary The 400 Million (1939). But, even by the 1930s, the stat had been around for a long time – Tong Lam quotes the American diplomat John Watson Foster using it in 1903. It certainly seems to have been the given number for at least half a century. However, China did not have anything approaching an accurate population census during that period and, as is noted, various other estimates differed from the 400 million by several hundred million either way. 400 million could stand for any view of China you wanted – a massive potential enemy, market, drain on resources, opportunity or threat, depending on your outlook.

The Chinese too, both late Qing and Republicans – adopted the 400 million estimate – and again for a number of reasons – potential strength, potential weakness, untapped resources or possible crippling problems. Tong Lam calls the 400 million an “enumerative imaginery”, a “political trope” of various uses. But nobody has a better stat!

So we’re left with 400 million and it’s unlikely now that, in the absence of any useful census data from the period (to my knowledge), historical demographers can do much to improve on that. The 400 million stands!

Of course there had been earlier numbers – but these appear no less reliable. Around the middle of the nineteenth century many western sources quote the population at around 175 million to 200 million. However, the 400 million stat was being bandied about even then – the Rev. Spencer of Rockford, Ill, who’d been a missionary in China, told audiences in America in 1842 of the 400 million Chinese and an 1850 source quotes 450 million – it’s impossible the Chinese population didn’t change in a century!

After 1949 the estimates start to go up – Red Scare! possibly. Perhaps we might expect a dip or at least statis due to the Second World War. In 1950 most reports are talking about 500 million – that’s at least another 100 million between 1939 and 1949 with seven years of brutal and murderous war in between. These figures are important because almost immediately in the 1950s Mao, urged on by the Soviets, starts talking of the need to cut the population by 100 million – i.e. back to 400 million.

The Red Cross had a go at estimating the figures and found half a dozen surveys between 1950 and 1953 – they settled on an amazingly specific 482, 869, 687. The Chinese Red Army argued they were wrong and cited an equally amazingly specific stat of 492,530,000. The government said both were wrong and its was a rounded up 600 million, and growing at 20 million per year. Fast forward to 1960 and Beijing is now saying 650 million and predicting 900 million by 1980. 1965 sees 680-700 million commonly reported. By 1970 the 700 million stat is the most commonly used in newspapers. 1975 and Beijing says “almost 800 million”; 1980 and it’s 900 million and by 1985 the magic “billion” starts creeping in, as does the One-Child Policy.

That’s enough stats for me…from 400 million in the late 1930s to a billion by the 1980s – but perhaps more or less than 400 million in the 1930s and perhaps more or less than a billion by the mid-1980s!! I’m off to a dark room with a cold glass of water to calm down now!

Posted: October 14th, 2015 | No Comments »

I’ve blogged about the once famous Shanghai Emporium, a Chinese food store that was adjacent to the Shanghai restaurant on Soho’s Greek Street (here, here and here). Here’s a photograph taken inside the Pillars of Hercules pub (which is still going strong) from 24th November 1933. The Pillars of Hercules pub is itself is on Greek Street (see below) and the small alleyway that runs up its side is Manette Street (named after the Dickens character in Tale of Two Cities) that cuts through to Charing Cross Road by the side of the old Foyles bookshop. In this picture you can see out the side window, facing north, onto the Manette Street cut through and see the street signage for the old Shanghai Emporium was the building immediately to the north of the pub, i.e. up towards Soho Square. And so, as the gent in the picture is obviously saying, “cheers”…

Posted: October 12th, 2015 | No Comments »

Alexander Cordell is now best remembered for his series of books about the industrialisation of Wales, Rape of the Fair Country probably being the best remembered of his Welsh novels. But The Bright Cantonese, retitled The Deadly Eurasian for some subsequent editions and published by Victor Gollancz in 1967, is the story of Mei Kayling, a half-British, half-Chinese member of the Red Guard who is, in fact, a secret agent. It’s a product of its time following a heroic Red Guard trying to thwart a nuclear attack on China by the USA.

Though noted mostly for his Welsh writing, Cordell spent much of his youth in the Far East, particularly in Hong Kong, and had been born in Ceylon. He died in 1997 and his obituary in The Independent carried a good line, “Alexander Cordell was a popular writer whose novels were read by people who do not usually read novels.” He wrote two other novels located in China – The Sinews of Love (1965), which is set in Hong Kong, and The Dream and the Destiny (1975), about the Long March of Mao Tse-tung.