Posted: June 12th, 2014 | No Comments »

Interesting when you happen to pick up a novel that refers to an incident you’ve recently written about. So, if you happen to be interested in China’s role at the Paris Peace Conference and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1919, you’ll probably enjoy Robert Goddard’s The Ways of the World. The novel is the first in the author’s planned The Wide World trilogy concerning espionage and shady goings-on in the aftermath of World War One and featuring James “Max†Maxted, a former Great War flying ace caught up in Great Powers deception and general murkiness. Book one of the trilogy, The Ways of the World, takes place during the Paris Peace Conference in the spring of 1919 in that great city. One aspect of the book invokes one of the great mysteries of that period and offers a possible hypothesis that any readers of my recent Penguin China World War One series e-book Betrayal in Paris might find interesting.

Here’s the mystery. Obviously during WW1 Japan took advantage of the European Great Powers killing each other in France and Belgium to make a land grab at the former German concession of Tsingtao (Qingdao) and across Shantung (Shandong) province (if you didn’t know that see Jonathan Fenby’s new book on the incident here). Then, with China looking weak, Tokyo made its infamous and extortionist 21 Demands upon Peking. In 1917 China officially declared war on Germany and became a recognised Allied nation. At the Armistice China was awarded a seat at the Paris Peace Conference and came looking for restitution of its territory in Tsingtao and Shantung. They were to be disappointed and betrayed at Versailles – Japan kept hold of Tsingtao with Great Power (and US) acquiescence. That’s the above-the-surface story. Of course there’s also a below-the-surface tale….

The official leader of China’s delegation to Versailles was Lou Tseng-tsiang (Lu Zhengxiang), a veteran diplomat and former Chinese ambassador to the Russian Empire at St Petersburg (Petrograd). Lou sailed from China to France with a stopover in Tokyo. This worried some who considered Lou rather pro-Japanese and some of his masters in the Peking government to be to cosy with Tokyo too. Suspicions heightened when Lou had a two-hour private meeting with Japan’s foreign minister. It became a confused situation – the Japanese claimed that Lou had promised not to cause any trouble between China and Japan, while the Chinese side claimed Lou had not officially recognised the validity of Japan’s 21 Demands.

Then it all became the stuff of a spy book. Rumours appeared in the press of the apparent theft of a box of Chinese official documents in Tokyo during Lou’s stopover. The possible scenarios multiplied:

1) Lou had allowed the Japanese to take the documents to undermine China’s bargaining position over Shantung at Versailles – the reasoning? He was always pro-Japanese and probably worked for them or was bribed;

2) The Peking government had instructed Lou to let the box fall into Japanese hands – the reasoning? The Peking government had strong pro-Tokyo elements who thought an alliance of some sort with Japan would help them beat the Southern, alternative, government established in Canton by Sun Yat-sen. It was an unholy alliance for regime survival purposes;

3) The Japanese did indeed steal the box – the reasoning? Well, they would wouldn’t they, as they wanted to undermine China’s arguments in Paris;

4) The box was never stolen – the reasoning? Lou never confirmed he’d lost it, the Japanese never confirmed they had it and the whole thing was a tall tale thrown together to make Japan look bad and China look even more bullied by Tokyo in Paris.

Goddard, however, has a much more thrilling explanation for the contents of the missing box (which I’ll paraphrase to avoid any spoilers):

The box contained proof that Germany attempted to get Japan to switch sides in WW1 from the Allies to the Axis and so use the Japanese Navy to attack Hawaii and the Philippines thereby distracting America if and when it entered the war. The bait (which the Germans offered via the Chinese – OK, a bit convoluted this – why not go direct to Tokyo?) was German controlled lands in the event of victory in the Pacific, Russian Far East and, rather daringly, Australia and New Zealand. Goddard supposes the Japanese agreed and signed a letter to that effect which was in Chinese hands, but then reneged just prior to America’s entry into the war. Still the letter would have been majorly embarrassing and would, if released, have undermined Great Power support for Japan in Paris and probably seen the Europeans side with China over Shantung and not Japan. Thus they stole the letter back during Lou’s stopover en route to Paris.

Fiendish! And a nice theory….maybe the letter will turn up one day; maybe it won’t; probably it never existed! But then was a Chinese box really stolen in 1918 in Tokyo and, if so, what was in it?

Posted: June 11th, 2014 | No Comments »

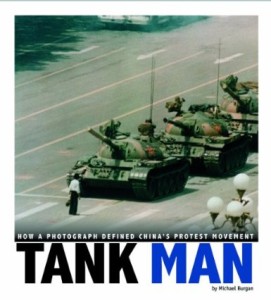

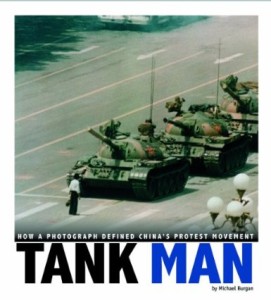

Another Tiananmen book for the 25th anniversary of the massacre. This book looks specifically at that iconic image (iconic in the West anyway thanks to the diligence of the Net Nanny in China!)…

No one knew his name. But soon millions would know about his bravery. For almost two months in spring 1989, Beijing s Tiananmen Square had been the site of growing protests against China’s hardline communist government. In early June, China s leaders had had enough. In a matter of days soldiers cleared the square. They used sticks and cattle prods. They shot rubber bullets, then real ones. They used bayonets. Student protesters fought back with firebombs and rocks, but they were no match for the soldiers. Gunfire still rang out in parts of Beijing, but China s leaders felt in control. As tanks rumbled through the streets near Tiananmen Square, a man in a white shirt came suddenly into view. He held up his right hand, like a police officer trying to halt traffic. The first huge tank in a row of four stopped just a few feet in front of the man. The tanks behind it stopped as well. Photographer Jeff Widener took a picture of the brave protester halting the huge armored fighting vehicles. The image was soon sent around the world, becoming one of the most famous photographs ever.”

No one knew his name. But soon millions would know about his bravery. For almost two months in spring 1989, Beijing s Tiananmen Square had been the site of growing protests against China’s hardline communist government. In early June, China s leaders had had enough. In a matter of days soldiers cleared the square. They used sticks and cattle prods. They shot rubber bullets, then real ones. They used bayonets. Student protesters fought back with firebombs and rocks, but they were no match for the soldiers. Gunfire still rang out in parts of Beijing, but China s leaders felt in control. As tanks rumbled through the streets near Tiananmen Square, a man in a white shirt came suddenly into view. He held up his right hand, like a police officer trying to halt traffic. The first huge tank in a row of four stopped just a few feet in front of the man. The tanks behind it stopped as well. Photographer Jeff Widener took a picture of the brave protester halting the huge armored fighting vehicles. The image was soon sent around the world, becoming one of the most famous photographs ever.”

Posted: June 11th, 2014 | No Comments »

A slice of blatant self-promotion today I’m afraid, but if you’re interested in China’s role at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the arguments over Shandong and China’s betrayal by the Great Powers and the USA then this interview with myself for Beijing Cream regarding my e-book in the Penguin China World War One Series – Betrayal in Paris: How the Treaty of Versailles Led to China’s Long Revolution – might be of interest. The ebook is available here on Amazon.com and here on Amazon.co.uk

Posted: June 10th, 2014 | No Comments »

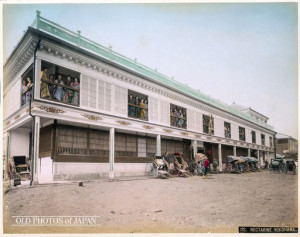

And just to finish up on old Yokohama….Although a treaty port, Yokohama never quite took on the international characteristics of a Shanghai, but it didn’t do bad and parts of its were indeed as “bad” as Shanghai at its height in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century….

The Yokohama Bund

A Yokohama chemist’s shop

The Yokohama Custom’s House in the snow

Yokohama’s skyline

Yokohama’s pier area

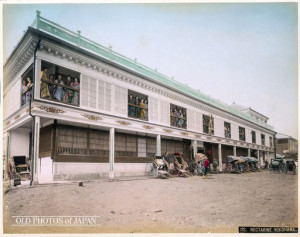

The nearby Yoshiwara red light district

Posted: June 8th, 2014 | No Comments »

(carrying on from yesterday’s post on the Nectarine brothel…)

In 1900 the American Consul General Edward C. Bellows wrote to the State Department to inform them of the death of James Curtis, an American citizen. Boston-born, 40-year-old Curtis, who had no known relatives, had died of alcoholism in Yokohama’s General Hospital on a charity ward. Bellows clearly knew Curtis, recording on his Report of the Death of an American Citizen form sent to Washington that he had, ‘…come to Japan in 1887, since which date he has led the dissolute life of a crimp.’

Â

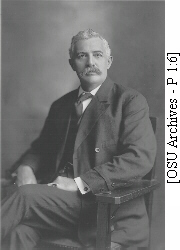

In 1905 Bellows’ successor as American Consul General in Yokohama, Henry B. Miller (pictured below) didn’t mince his words when asked by the State Department for a report on the presence or otherwise of American prostitutes in the port. Miller was a tough and plain spoken businessman who had started out in the Oregon lumber business, got himself elected a member of the Oregon legislature and then an appointment as U.S. Consul General to Chungking at the head of the Yangtze before moving to Newchwang, a small treaty port in north east China (where the Great Wall meets the sea) and finally Yokohama. In a fairly lengthy, but highly revealing, report on the local prostitution scene (at a time when Gracie may still have been there shortly before moving to Shanghai) Miller wrote:

Â

‘The police report to me that there are now in this city several houses under suspicion of harboring American prostitutes, one contains four women known to be Americans…Besides these there is another house containing one French woman and another with a Chinese woman under suspicion as prostitutes. These women are generally well known upon the streets and advertise by letters to the various hotel guests. In addition to these permanent places there are numbers of women belonging to this class travelling in Japan, and almost every steamer coming from San Francisco brings one or more prostitutes to the Orient and it is reported that proprietresses often pay their passage over. Many of these women are Americans, while numbers of them claim American citizenship, but are of other nationalities. I think it is perhaps true that the great per cent of foreign prostitutes coming here claim American citizenship.’

Posted: June 7th, 2014 | No Comments »

(Carrying on from yesterday’s post on Yokohama….)

Yokohama was by far the most Western-oriented Japanese city and for some time a particularly lucrative venue for American-run bordellos causing the American authorities in the port no end of headaches. The foreign community was small – the local Japanese Police Department of Kanagawa Prefecture (of which Yokohama was the capital) recorded approximately 6,000 foreigners resident in1903, though nearly 4,000 of these were Chinese with just 527 Americans along with about a thousand Brits, slightly less than 300 Germans, 155 French and a sprinkling of other Europeans.

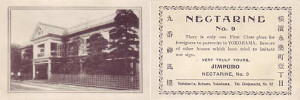

The famous Jimpuro, or Number Nine brothel in Yokohama – also known as the Nectarine which opened in 1872. The enterprising Japanese owners also opened a branch catering to foreigners only in the 1890s, run by a madam known to all as Mother Jesus, and targeting them specifically as the invite below shows – the Nectarine was well known enough to get a mention in Rudyard Kipling’s 1893 poem McAndrew’s Hymn.

Posted: June 6th, 2014 | No Comments »

As I blogged yesterday about Eric Han’s new book, Rise of a Japanese Chinatown: Yokohama, 1894-1972, I thought I’d offer up a few more images of Yokohama in its treaty port heyday.

As America became the dominant foreign power trading with Japan, American Girls appeared in American-run bordellos in Yokohama and neighbouring Kawasaki where brothels operated by San Francisco Madams operated alongside those run by Japanese organised crime groups in various locations including the port’s major red light district – Nanaken-machi. Here English speaking Japanese girls, targeted foreigners specifically. Yokohama had become a treaty port as early as 1858 following treaties with the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, Russia and France – extrality rights were included in the treaties.

As ever in a port full of foreign sailors brothels had been in existence since shortly after America’s Commodore Perry had opened Yokohama to foreign trade. British, French, Russian and American sailors patronised the grog shops, called “pot-housesâ€, and brothels of the area on the edge of the port’s Chinatown. The areabecame known as Blood Town or Dirty Town where the sailors drunk themselves blind, enjoyed the girls and fought each other in the street. Yokohama soon had the reputation of being the Wild West of Japan with a cast of, mostly American, driftwood, beachcombers and ne’er–do–wells following the sailors’ wallets.

The port prospered though and, by the 1890s, Yokohama was relatively modern by Japanese standards. The most respectable foreigners lived up on “the Bluff†in large European-style houses, gas lamps lit the streets, there was a rail line to Tokyo (which passed right by the windows of the red light district giving passengers cause to ogle or blush depending on their temperament) and the Grand Hotel (which as you can see below went through some remodellings) was considered one of the Orient’s best establishments.

Posted: June 6th, 2014 | No Comments »

Yokohama’s history as a treaty port is often overlooked and a little forgotten – Eric Han’s new history restores some of that….

Rise of a Japanese Chinatown is the first English-language monograph on the history of a Chinese immigrant community in Japan. It focuses on the transformations of that population in the Japanese port city of Yokohama from the Sino–Japanese War of 1894–1895 to the normalization of Sino–Japanese ties in 1972 and beyond. Eric C. Han narrates the paradoxical story of how, during periods of war and peace, Chinese immigrants found an enduring place within a monoethnic state.

This study makes a significant contribution to scholarship on the construction of Chinese and Japanese identities and on Chinese migration and settlement. Using local newspapers, Chinese and Japanese government records, memoirs, and conversations with Yokohama residents, it retells the familiar story of Chinese nation building in the context of Sino-Japanese relations. But it builds on existing works by directing attention as well to non-elite Yokohama Chinese, those who sheltered revolutionary activists and served as an audience for their nationalist messages. Han also highlights contradictions between national and local identifications of these Chinese, who self-identified as Yokohama-ites (hamakko) without claiming Japaneseness or denying their Chineseness. Their historical role in Yokohama’s richly diverse cosmopolitan past can offer insight into a future, more inclusive Japan.