Posted: January 22nd, 2012 | No Comments »

The annual Beijing International Literary Festival 2012 is on throughout March up at the Beijing Bookworm and it’s bigger than ever and spread over more venues, with more authors than previously. I’m there doing a bunch of stuff of which more details later – but here’s a link to their newly launched site with all details for the early birds who work out their lives sensibly in good time to get tickets for things!

Posted: January 21st, 2012 | 1 Comment »

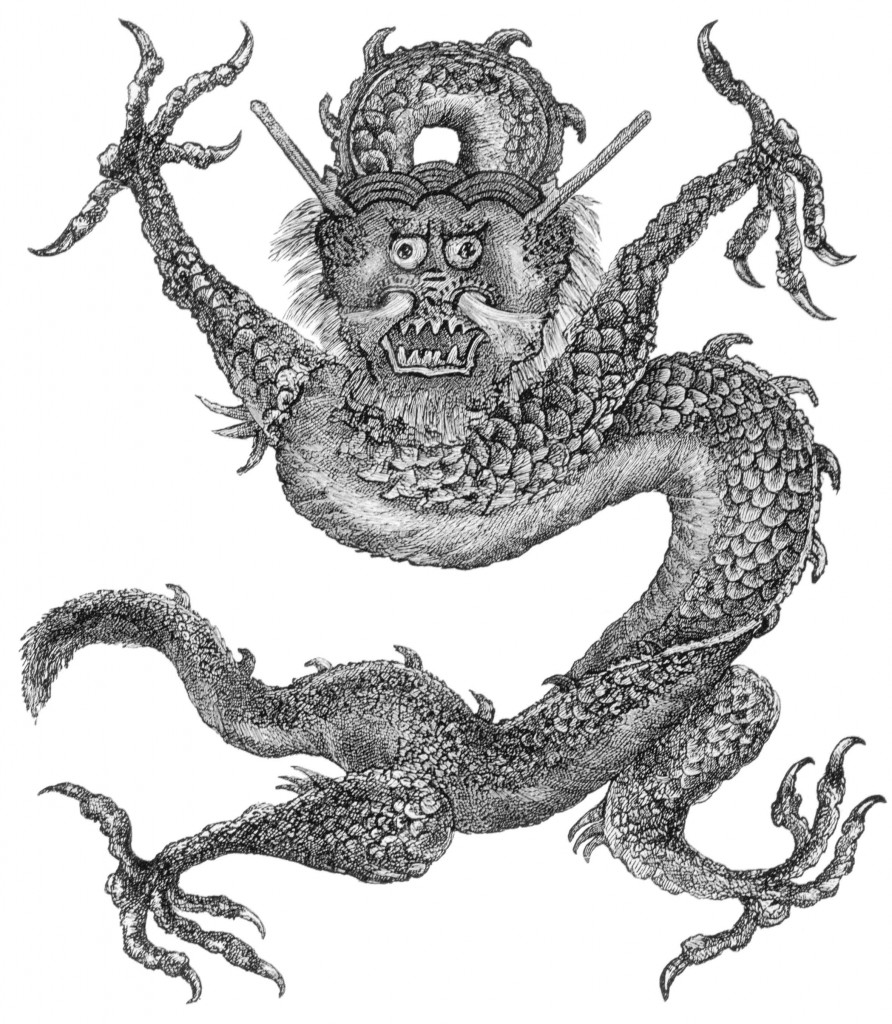

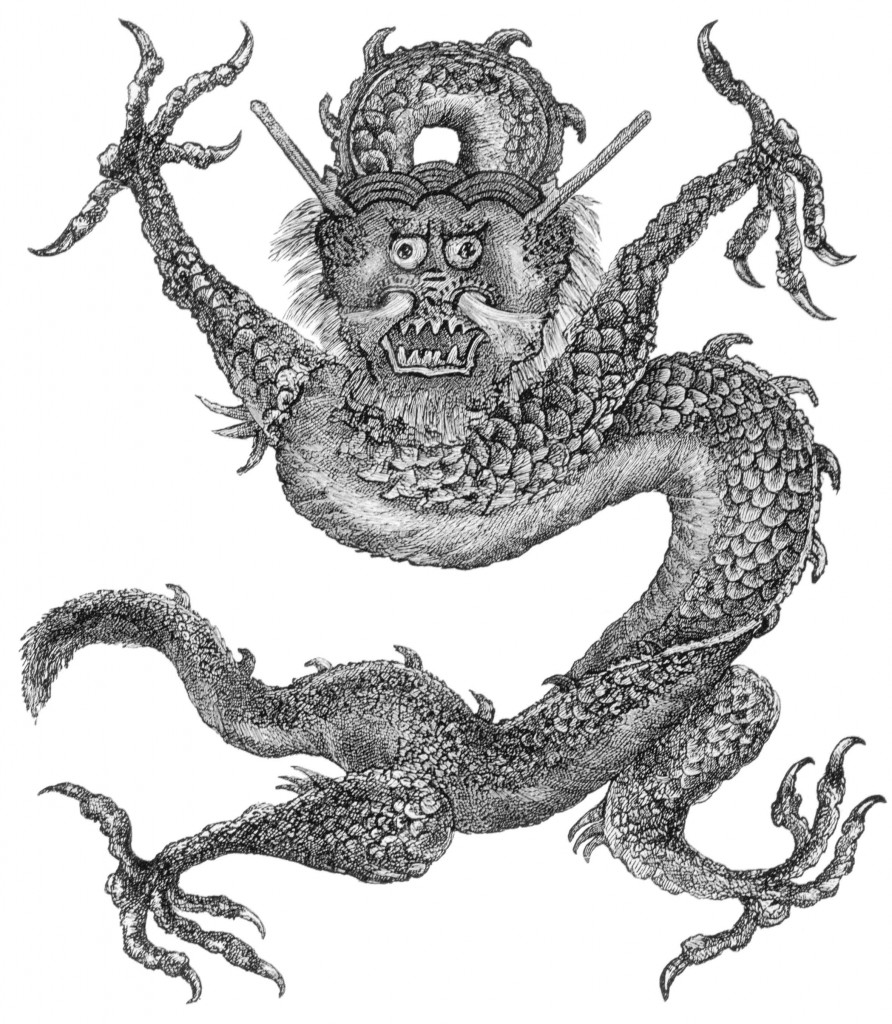

In 2011 I got my own dragon!! A very cool dragon that appeared on the front of Midnight in Peking. So I’m well prepared for the year of the dragon! Happy new year to all and sundry.

Posted: January 21st, 2012 | No Comments »

They just launched the Perth Writers Festival 2012 Programme – I’ll be speaking at a few events, mostly panels if anyone’s around Western Australia. The full programme is now available on their website. The festival takes place on the weekend from February 23 – 26 2012 at The University of Western Australia. I’ll be in Canberra and then Adelaide after Perth, details on those events to follow.

Posted: January 21st, 2012 | No Comments »

Remiss of me not to have noted this earlier but my book Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists From Opium War to Mao (here in English hard copy and here in English in an excellently low priced Kindle edition) is now available in a Chinese edition. I’m told it’s been seen in bookshops around Shanghai and Beijing and is here on Amazon.com.cn for a mere RMB27. Chinese readers have given me 4 out of a possible 5 stars and reader reviews give it a bunch of 5 stars so that’s nice!

Thanks to everyone at Beijing Mediatime Books for all their efforts in getting the book out in Chinese.

Posted: January 20th, 2012 | No Comments »

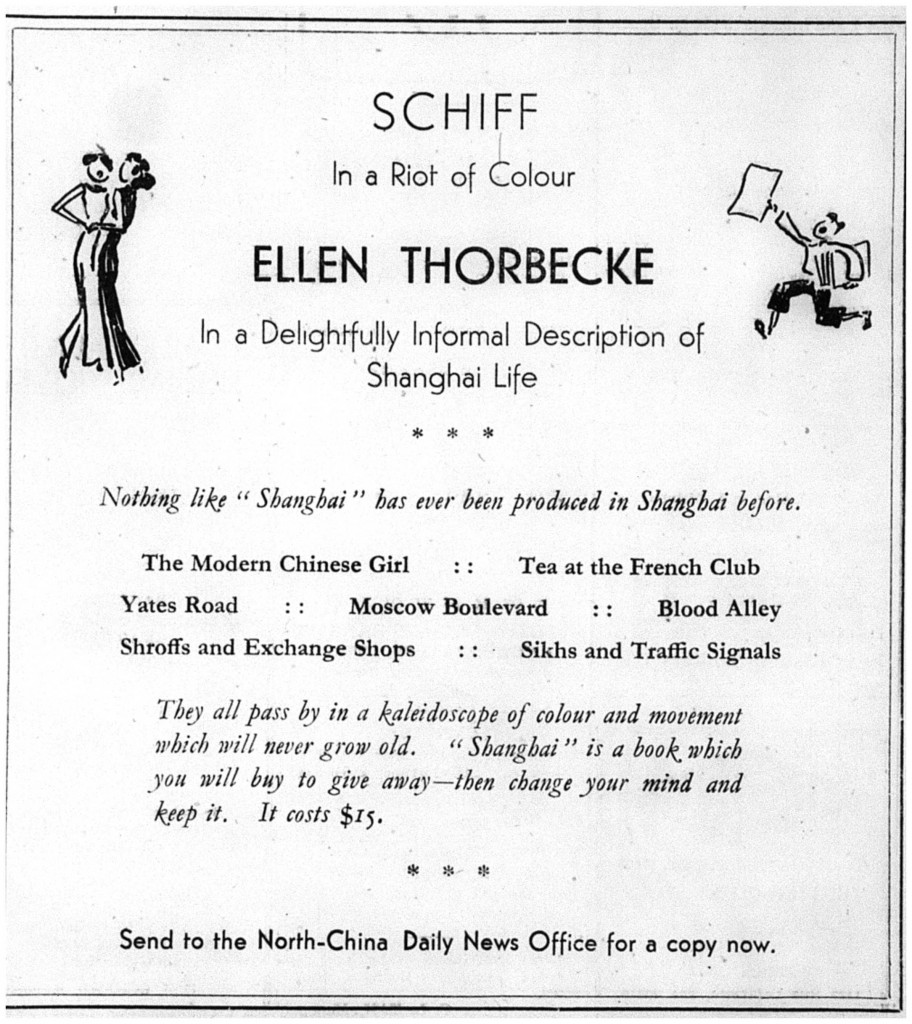

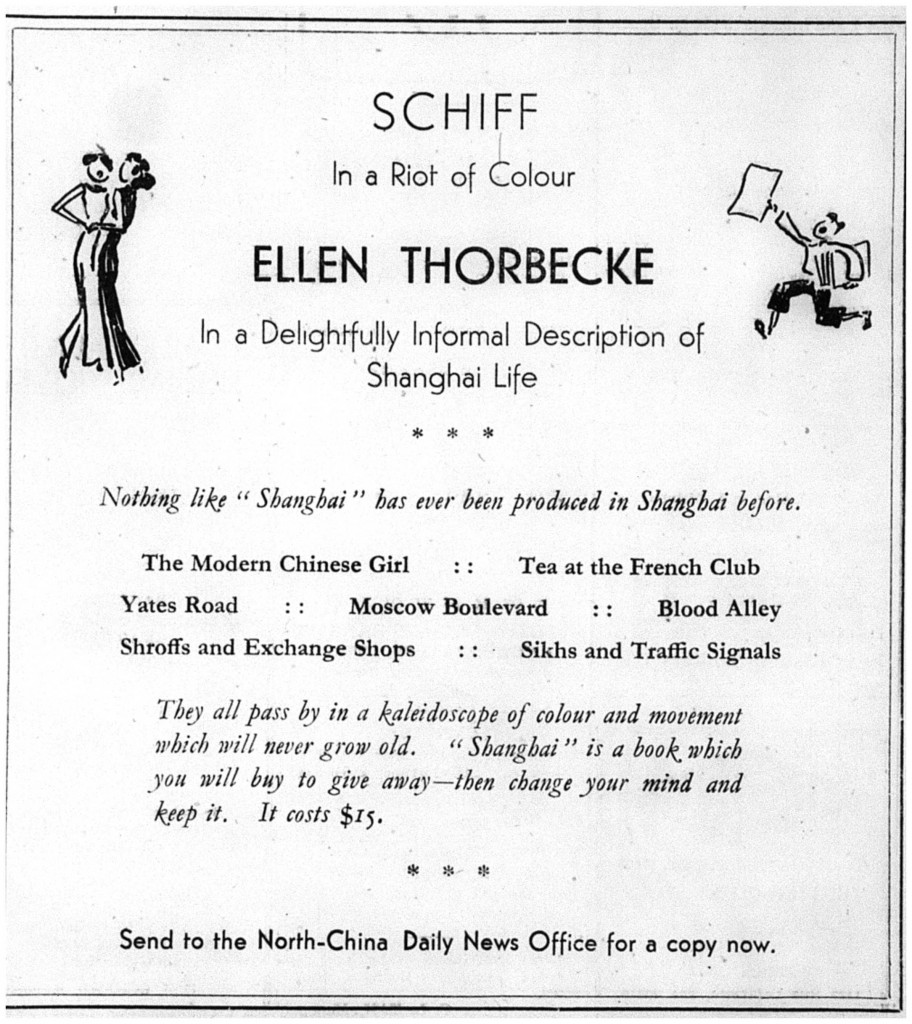

Ellen Thorbeck’s Shanghai: Photographed and Depicted by Ellen Thorbecke with Sketches by Schiff is a great, but rarely seen these days, book. Shanghai’s great newspaper, ‘the old lady of the Bund’, The North-China Daily News actually published it in 1940. Thorbecke and Schiff (an Austrian artist working in Shanghai) worked together several times on books about Hong Kong and Peking as well as Shanghai – their great 1934 guide to Peking was a large book – Hong Kong and Shanghai were more manageable publications. Thorbecke, a German who married a Dutch Ambassador to China, was an accomplished photographer and photo-journalist who worked in China a long time. The trademark style of using Schiff’s amusing colourful sketches of people over, say, a Thorbecke photograph of Jessfield Park (Zhangshan Park) was considered sacrilege by some photographers but the public liked thre combination (and it would be nice to see some of Shanghai’s photography and art community try something similar today perhaps). The mix of essays, photos, drawings and little epigrams was very popular and sold really well reflecting a taste for art-nouveau styles in Shanghai and a fondness for the eccentric among China Coasters.

Anyway, below is an advert from the North-China Daily News advertising the book in 1940 – it includes some more Schiff sketches – ‘tea at the French Club’, ‘Blood Alley’, ‘Moscow Boulevard’ – come on, how can you not rush credit card in hand to your local antiquarian bookseller!! However, just checking Abe Books you might need US$800 for a good copy!!

Posted: January 19th, 2012 | No Comments »

It was a gruelling four hours of questioning, a lengthy time to be under the spotlight as the members of the RAS Shanghai Book Club grilled me on the details of the murder of Pamela Werner, 1937 Peking, the police investigation, my investigation and that most mysterious thing of all…my prose style!! Still, despite being jetlagged and having had a long day it was brilliant that the RAS Book Club was oversubscribed and so we had two two-hour sessions instead of one! The Puli Hotel library was a great venue too. A massive thanks to the Royal Asiatic Society for organising it and for all those who came – it’s amazing to meet readers who have shared your fascination, horror and anger at what happened to Pamela in 1937.

Posted: January 19th, 2012 | 1 Comment »

Another Chinois poem from Vachel Lindsay following on from yesterday’s poem. This is an interesting piece criticising foreigners in China but with plenty of Chinois style too. I’m no poetry critic so I’ll just let you read it – I think it calls for a somewhat dramatic voice in your head! There are a lot of quite contemporary references in the piece too. Lindsay’s biographer and critic Edgar Lee Masters in his book Vachel Lindsay: A Poet in America comments that Shantung, or the Empire of China is Falling Down is inferior to The Chinese Nightingale – you can decide for yourselves.

Shantung, or the Empire of China is Falling Down

I

Now let the generations pass—

Like sand through Heaven’s blue hour-glass.

In old Shantung,

By the capital where poetry began,

Near the only printing presses known to man,

Young Confucius walks the shore

On a sorrowful day.

The town, all books, is tumbling down

Through the blue bay.

The bookworms writhe

From rusty musty walls.

They drown themselves like rabbits in the sea.

Venomous foreigners harry mandarins

With pitchfork, blunderbuss and snickersnee.

In the book-slums there is thunder;

Gunpowder, that sad wonder,

Intoxicates the knights and beggar-men.

The old grotesques of war begin again:

Rebels, devils, fairies, are set free.

So…

Confucius hears a carol and a hum:

A picture sea-child whirs from off his fan

In one quick breath of peach-bloom fantasy,

Then, in an instant bows the reverent knee —

A full-grown sweetheart, chanting his renown.

And then she darts into the Yellow Sea,

Calling, calling:

“Sage with holy brow,

Say farewell to China now;

Live like the swine,

Leave off your scholar-gown!

This city of books is falling, falling,

The Empire of China is crumbling down.”

II

Confucius, Confucius, how great was Confucius—

The sage of Shantung, and the master of Mencius?

Alexander fights the East.

Just as the Indus turns him back

He hears of tempting lands beyond,

With sword-swept cities on the rack

With crowns outshining India’s crown:

The Empire of China, crumbling down.

Later the Roman sibyls say:

“Egypt, Persia and Macedon,

Tyre and Carthage, passed away;

And the Empire of China is crumbling down.

Rome will never crumble down.”

III

See how the generations pass—

Like sand through Heaven’s blue hour-glass.

Arthur waits on the British shore

One thankful day,

For Galahad sails back at last

To Camelot Bay.

The pure knight lands and tells the tale:

“Far in the east

A sea-girl led us to a king,

The king to a feast,

In a land where poppies bloom for miles,

Where books are made like bricks and tiles.

I taught that king to love your name—

Brother and Christian he became.

“His Town of Thunder-Powder keeps

A giant hound that never sleeps,

A crocodile that sits and weeps.

“His Town of Cheese the mouse affrights

With fire-winged cats that light the nights.

They glorify the land of rust;

Their sneeze is music in the dust.

(And deep and ancient is the dust.)

“All towns have one same miracle

With the Town of Silk, the capital—

Vast book-worms in the book-built walls.

Their creeping shakes the silver halls;

They look like cables, and they seem

Like writhing roots on trees of dream.

Their sticky cobwebs cross the street,

Catching scholars by the feet,

Who own the tribes, yet rule them not,

Bitten by book-worms till they rot.

Beggars and clowns rebel in might

Bitten by book-worms till they fight.”

Arthur calls to his knights in rows:

“I will go if Merlin goes;

These rebels must be flayed and sliced—

Let us cut their throats for Christ.”

But Merlin whispers in his beard:

“China has witches to be feared.”

Arthur stares at the sea-foam’s rim

Amazed. The fan-girl beckons him!—

That slender and peculiar child

Mongolian and brown and wild.

His eyes grow wide, his senses drown.

She laughs in her wing, like the sleeve of a gown.

She lifts a key of crimson stone:

“The Great Gunpowder-town you own.”

She lifts a key with chains and rings:

“I give the town where cats have wings.”

She lifts a key as white as milk:

“This unlocks the Town of Silk”—

Throws forty keys at Arthur’s feet:

“These unlock the land complete.”

Then, frightened by suspicious knights,

And Merlin’s eyes like altar-lights,

And the Christian towers of Arthur’s town,

She spreads blue fins — she whirs away;

Fleeing far across the bay,

Wailing through the gorgeous day:

“My sick king begs

That you save his crown

And his learnèd chiefs from the worm and clown—

The Empire of China is crumbling down.”

IV

Always the generations pass,

Like sand through Heaven’s blue hour-glass!

The time the King of Rome is born—

Napoleon’s son, that eaglet thing—

Bonaparte finds beside his throne

One evening, laughing in her wing,

The Chinese sea-child; and she cries,

Breaking his heart with emerald eyes

And fairy-bred unearthly grace:

“Master, take your destined place—

Across white foam and water blue

The streets of China call to you:

The Empire of China is crumbling down.”

Then he bends to kiss her mouth,

And gets but incense, dust, and drouth.

Custodians, custodians!

Mongols and Manchurians!

Christians, wolves, Mohammedans!

In hard Berlin they cried: “O King,

China’s way is a shameful thing!”

In Tokio they cry: “O King,

China’s way is a shameful thing!”

And thus our song might call the roll

Of every land from pole to pole,

And every rumor known to time

Of China doddering — or sublime.

V

Slowly the generations pass—

Like sand through Heaven’s blue hour-glass.

So let us find tomorrow now:

Our towns are gone;

Our books have passed; ten thousand years

Have thundered on.

The Sphinx looks far across the world

In fury black:

She sees all western nations spent

Or on the rack.

Eastward she sees one land she knew

When from the stone

Priests of the sunrise carved her out

And left her lone.

She sees the shore Confucius walked

On his sorrowful day:

Impudent foreigners rioting,

In the ancient way;

Officials, futile as of old,

Have gowns more bright;

Bookworms are fiercer than of old,

Their skins more white;

Dust is deeper than of old,

More bats are flying;

More songs are written than of old—

More songs are dying.

Where Galahad found forty towns

Now fade and glare

Ten thousand towns with book-tiled roof

And garden-stair,

Where beggars’ babies come like showers

Of classic words:

They rule the world of immortal brooks

And magic birds.

The lion Sphinx roars at the sun:

“I hate this nursing you have done!

The meek inherit the earth too long—

When will the world belong to the strong?”

She soars; she claws his patient face—

The girl-moon screams at the disgrace.

The sun’s blood fills the western sky;

He hurries not, and will not die.

The baffled Sphinx, on granite wings,

Turns now to where young China sings.

One thousand of ten thousand towns

Go down before her silent wrath;

Yet even lion-gods may faint

And die upon their brilliant path.

She sees the Chinese children romp

In dust that she must breathe and eat.

Her tongue is reddened by its lye;

She craves its grit, its cold and heat.

The Dust of Ages holds a glint

Of fire from the foundation-stones,

Of spangles from the sun’s bright face,

Of sapphires from earth’s marrow-bones.

Mad-drunk with it, she ends her day—

Slips when a high sea-wall gives way,

Drowns in the cold Confucian sea

Where the whirring fan-girl first flew free.

In the light of the maxims of Chesterfield, Mencius,

Wilson, Roosevelt, Tolstoy, Trotsky,

Franklin or Nietzsche, how great was Confucius?

“Laughing Asia” brown and wild,

That lyric and immortal child,

His fan’s gay daughter, crowned with sand,

Between the water and the land

Now cries on high in irony,

With a voice of night-wind alchemy:

“O cat, O sphinx,

O stony-face,

The joke is on Egyptian pride,

The joke is on the human race:

‘The meek inherit the earth too long—

When will the world belong to the strong?’

I am born from off the holy fan

Of the world’s most patient gentleman.

So answer me,

O courteous sea!

O deathless sea!”

And thus will the answering Ocean call:

“China will fall,

The Empire of China will crumble down,

When the Alps and the Andes crumble down;

When the sun and the moon have crumbled down,

The Empire of China will crumble down,

Crumble down.”

Posted: January 18th, 2012 | No Comments »

Don’t know about you but I think in 2012 we should all have a little more poetry in our lives. And so, as this is the China Rhyming blog, we have a little poetry inspired by Chinoiserie from the poet Vachel Lindsay (1879-1931). Lindsay was a somewhat well known poet in his heyday and is considered the father of the modern American singing verse tradition. There is more on him here. I am not sure where his interest in China came from though he was published by Harriet Monroe who had a significant interest in China, Chinese poetry and the Chinoiserie tradition. Anyway, here is The Chinese Nightingale from around 1917.

“How, how,” he said. “Friend Chang,” I said,

“San Francisco sleeps as the dead —

Ended license, lust and play:

Why do you iron the night away?

Your big clock speaks with a deadly sound,

With a tick and a wail till dawn comes round.

While the monster shadows glower and creep,

What can be better for man than sleep?”

“I will tell you a secret,” Chang replied;

“My breast with vision is satisfied,

And I see green trees and fluttering wings,

And my deathless bird from Shanghai sings.”

Then he lit five fire-crackers in a pan.

“Pop, pop,” said the fire-crackers, “cra-cra-crack.”

He lit a joss stick long and black.

Then the proud gray joss in the corner stirred;

On his wrist appeared a gray small bird,

And this was the song of the gray small bird:

“Where is the princess, loved forever,

Who made Chang first of the kings of men?”

And the joss in the corner stirred again;

And the carved dog, curled in his arms, awoke,

Barked forth a smoke-cloud that whirled and broke.

It piled in a maze round the ironing-place,

And there on the snowy table wide

Stood a Chinese lady of high degree,

With a scornful, witching, tea-rose face . . .

Yet she put away all form and pride,

And laid her glimmering veil aside

With a childlike smile for Chang and for me.

The walls fell back, night was aflower,

The table gleamed in a moonlit bower,

While Chang, with a countenance carved of stone,

Ironed and ironed, all alone.

And thus she sang to the busy man Chang:

“Have you forgotten . . .

Deep in the ages, long, long ago,

I was your sweetheart, there on the sand —

Storm-worn beach of the Chinese land?

We sold our grain in the peacock town

Built on the edge of the sea-sands brown —

Built on the edge of the sea-sands brown . . .

“When all the world was drinking blood

From the skulls of men and bulls

And all the world had swords and clubs of stone,

We drank our tea in China beneath the sacred spice-trees,

And heard the curled waves of the harbor moan.

And this gray bird, in Love’s first spring,

With a bright-bronze breast and a bronze-brown wing,

Captured the world with his carolling.

Do you remember, ages after,

At last the world we were born to own?

You were the heir of the yellow throne —

The world was the field of the Chinese man

And we were the pride of the Sons of Han?

We copied deep books and we carved in jade,

And wove blue silks in the mulberry shade . . .”

“I remember, I remember

That Spring came on forever,

That Spring came on forever,”

Said the Chinese nightingale.

My heart was filled with marvel and dream,

Though I saw the western street-lamps gleam,

Though dawn was bringing the western day,

Though Chang was a laundryman ironing away . . .

Mingled there with the streets and alleys,

The railroad-yard and the clock-tower bright,

Demon clouds crossed ancient valleys;

Across wide lotus-ponds of light

I marked a giant firefly’s flight.

And the lady, rosy-red,

Flourished her fan, her shimmering fan,

Stretched her hand toward Chang, and said:

“Do you remember,

Ages after,

Our palace of heart-red stone?

Do you remember

The little doll-faced children

With their lanterns full of moon-fire,

That came from all the empire

Honoring the throne? —

The loveliest fete and carnival

Our world had ever known?

The sages sat about us

With their heads bowed in their beards,

With proper meditation on the sight.

Confucius was not born;

We lived in those great days

Confucius later said were lived aright . . .

And this gray bird, on that day of spring,

With a bright-bronze breast, and a bronze-brown wing,

Captured the world with his carolling.

Late at night his tune was spent.

Peasants,

Sages,

Children,

Homeward went,

And then the bronze bird sang for you and me.

We walked alone. Our hearts were high and free.

I had a silvery name, I had a silvery name,

I had a silvery name — do you remember

The name you cried beside the tumbling sea?”

Chang turned not to the lady slim —

He bent to his work, ironing away;

But she was arch, and knowing and glowing,

And the bird on his shoulder spoke for him.

“Darling . . . darling . . . darling . . . darling . . .”

Said the Chinese nightingale.

The great gray joss on a rustic shelf,

Rakish and shrewd, with his collar awry,

Sang impolitely, as though by himself,

Drowning with his bellowing the nightingale’s cry:

“Back through a hundred, hundred years

Hear the waves as they climb the piers,

Hear the howl of the silver seas,

Hear the thunder.

Hear the gongs of holy China

How the waves and tunes combine

In a rhythmic clashing wonder,

Incantation old and fine:

`Dragons, dragons, Chinese dragons,

Red fire-crackers, and green fire-crackers,

And dragons, dragons, Chinese dragons.'”

Then the lady, rosy-red,

Turned to her lover Chang and said:

“Dare you forget that turquoise dawn,

When we stood in our mist-hung velvet lawn,

And worked a spell this great joss taught

Till a God of the Dragons was charmed and caught?

From the flag high over our palace home

He flew to our feet in rainbow-foam —

A king of beauty and tempest and thunder

Panting to tear our sorrows asunder:

A dragon of fair adventure and wonder.

We mounted the back of that royal slave

With thoughts of desire that were noble and grave.

We swam down the shore to the dragon-mountains,

We whirled to the peaks and the fiery fountains.

To our secret ivory house we were borne.

We looked down the wonderful wing-filled regions

Where the dragons darted in glimmering legions.

Right by my breast the nightingale sang;

The old rhymes rang in the sunlit mist

That we this hour regain —

Song-fire for the brain.

When my hands and my hair and my feet you kissed,

When you cried for your heart’s new pain,

What was my name in the dragon-mist,

In the rings of rainbowed rain?”

“Sorrow and love, glory and love,”

Said the Chinese nightingale.

“Sorrow and love, glory and love,”

Said the Chinese nightingale.

And now the joss broke in with his song:

“Dying ember, bird of Chang,

Soul of Chang, do you remember? —

Ere you returned to the shining harbor

There were pirates by ten thousand

Descended on the town

In vessels mountain-high and red and brown,

Moon-ships that climbed the storms and cut the skies.

On their prows were painted terrible bright eyes.

But I was then a wizard and a scholar and a priest;

I stood upon the sand;

With lifted hand I looked upon them

And sunk their vessels with my wizard eyes,

And the stately lacquer-gate made safe again.

Deep, deep below the bay, the sea-weed and the spray,

Embalmed in amber every pirate lies,

Embalmed in amber every pirate lies.”

Then this did the noble lady say:

“Bird, do you dream of our home-coming day

When you flew like a courier on before

From the dragon-peak to our palace-door,

And we drove the steed in your singing path —

The ramping dragon of laughter and wrath:

And found our city all aglow,

And knighted this joss that decked it so?

There were golden fishes in the purple river

And silver fishes and rainbow fishes.

There were golden junks in the laughing river,

And silver junks and rainbow junks:

There were golden lilies by the bay and river,

And silver lilies and tiger-lilies,

And tinkling wind-bells in the gardens of the town

By the black-lacquer gate

Where walked in state

The kind king Chang

And his sweetheart mate . . .

With his flag-born dragon

And his crown of pearl . . . and . . . jade,

And his nightingale reigning in the mulberry shade,

And sailors and soldiers on the sea-sands brown,

And priests who bowed them down to your song —

By the city called Han, the peacock town,

By the city called Han, the nightingale town,

The nightingale town.”

Then sang the bird, so strangely gay,

Fluttering, fluttering, ghostly and gray,

A vague, unravelling, final tune,

Like a long unwinding silk cocoon;

Sang as though for the soul of him

Who ironed away in that bower dim: —

“I have forgotten

Your dragons great,

Merry and mad and friendly and bold.

Dim is your proud lost palace-gate.

I vaguely know

There were heroes of old,

Troubles more than the heart could hold,

There were wolves in the woods

Yet lambs in the fold,

Nests in the top of the almond tree . . .

The evergreen tree . . . and the mulberry tree . . .

Life and hurry and joy forgotten,

Years on years I but half-remember . . .

Man is a torch, then ashes soon,

May and June, then dead December,

Dead December, then again June.

Who shall end my dream’s confusion?

Life is a loom, weaving illusion . . .

I remember, I remember

There were ghostly veils and laces . . .

In the shadowy bowery places . . .

With lovers’ ardent faces

Bending to one another,

Speaking each his part.

They infinitely echo

In the red cave of my heart.

`Sweetheart, sweetheart, sweetheart,’

They said to one another.

They spoke, I think, of perils past.

They spoke, I think, of peace at last.

One thing I remember:

Spring came on forever,

Spring came on forever,”

Said the Chinese nightingale.

Vachel Lindsay 1879-1931

Vachel Lindsay 1879-1931