Posted: January 29th, 2012 | No Comments »

My new year’s blogging resolution was to include more poetry on this blog – poetry with a Chinoiserie feel. I’ve posted a couple of Vachel Lindsay Chinois poems already (here and here) and today some of the great Ezra Pound. Pound had a long love affair with all things Oriental, Chinese and Chinoiserie and, of course, if a highly problematic character politically and ideologically. His early career in London saw him fascinated by Japan and China and become a translator, encouraged by he great Harriet Monroe.

This poem, entitled Ancient Wisdom, rather cosmic appeared (perhaps not first, but it’s where I first came across it) in the second (and last) edition of Blast, the short-lived but fascinating journal of the Vorticists produced ostensibly by Wyndham Lewis.This edition and poem appeared in 1915 and was entitled the “War Issue” and was hard hitting regarding the mechanised carnage in France at the time. The poem was later included in Pound’s collection Lustra, published a year after Blast (2) in 1916.

So-shu was the Japanese form of Chuang Chou (Tzu), a Chinese Taoist philosopher. This is Pound’s version of a Li Po poem about Chuang Tzu – Arthur Cooper, Li Po’s great translator also translated several versions of this poem. I’ve included Cooper’s translation below out of interest. Pound seems, to me, lighter and more concise but probably (and I’ve not checked the original) Cooper was more accurate to Li Po – but then Cooper was primarily a translator and Pound primarily a poet so perhaps not totally unexpected. So first Pound:

So-shu dreamed,

And having dreamed that he was a bird, a bee, and a butterfly,

He was uncertain why he should try to feel like anything else,

Hence his contentment.

— Ezra Pound

and now Cooper:

Did Chuang Chou dream

he was the butterfly

or the buterfly

that it was Chuang Chou?

In one body’s

metamorphoses

All is present

infinite virtue!

– Arthur Cooper

Pound – looking every bit as a radical poet should

Posted: January 28th, 2012 | No Comments »

James Palmer featured on this blog a few years ago for his great book The Bloody White Baron about Baron Ungen von Sternberg, the White Russian General who marauded across Mongolia. It was a rip roaring read about one of the twentieth century’s true nutters!! So, great to see his new book has finally hit the shelves – Heaven Cracks, Earth Shakes – about the 1976 Tangshan Earthquake. He’ll be in Shanghai and Suzhou at the Royal Asiatic Society in March apparently.

When an earthquake of historic magnitude leveled the industrial city of Tangshan in the summer of 1976, killing more than a half-million people, China was already gripped by widespread social unrest. As Mao lay on his deathbed, the public mourned the death of popular premier Zhou Enlai. Anger toward the powerful Communist Party officials in the Gang of Four, which had tried to suppress grieving for Zhou, was already potent; when the government failed to respond swiftly to the Tangshan disaster, popular resistance to the Cultural Revolution reached a boiling point.

In Heaven Cracks, Earth Shakes, acclaimed historian James Palmer tells the startling story of the most tumultuous year in modern Chinese history, when Mao perished, a city crumbled, and a new China was born.

Posted: January 27th, 2012 | No Comments »

A few years ago when I was writing my history of foreign journalists in China, Through the Looking Glass (hard copy or very competitively priced Kindle edition) I gathered together a series of rather odd comparisons of China by visitors to places back home that struck me as slightly silly, but fun. Perhaps one day I’ll get enough to do something with, but until then here’s a new one I came across recently and the others below from the great and the good for your delectation:

The great and usually erudite and brilliant W Somerset Maugham wrote:

‘…the bamboo, the Chinese bamboo, transformed by some magic of the mist, look just like the hops of Kentish field’

indeed!! But compared to the below perhaps not so odd:

- The American comedian Will Rogers compared the countryside around Harbin to Nebraska when he visited in the early 1930s.

- In the 1870s Jules Verne compared Hong Kong to a town in Kent or Surrey

- In 1933 Peter Fleming toured China and compared Chengde to Windsor

- He then compared Peking with Oxford for some reason!

- Later in 1938 Auden and Isherwood described the countryside around Guangzhou as reminiscent of the Severn Valley

- And then during his stay in China during the Second World War the (yet to be at the time) famous Sinologist Joseph Needham compared Fuzhou to Clapham and, perhaps most bizzarely, wartime Chongqing to Torquay!

And so…here’s Clapham in case you thought yourself transported via this photograph to Fuzhou with Joseph Needham!!

Posted: January 26th, 2012 | No Comments »

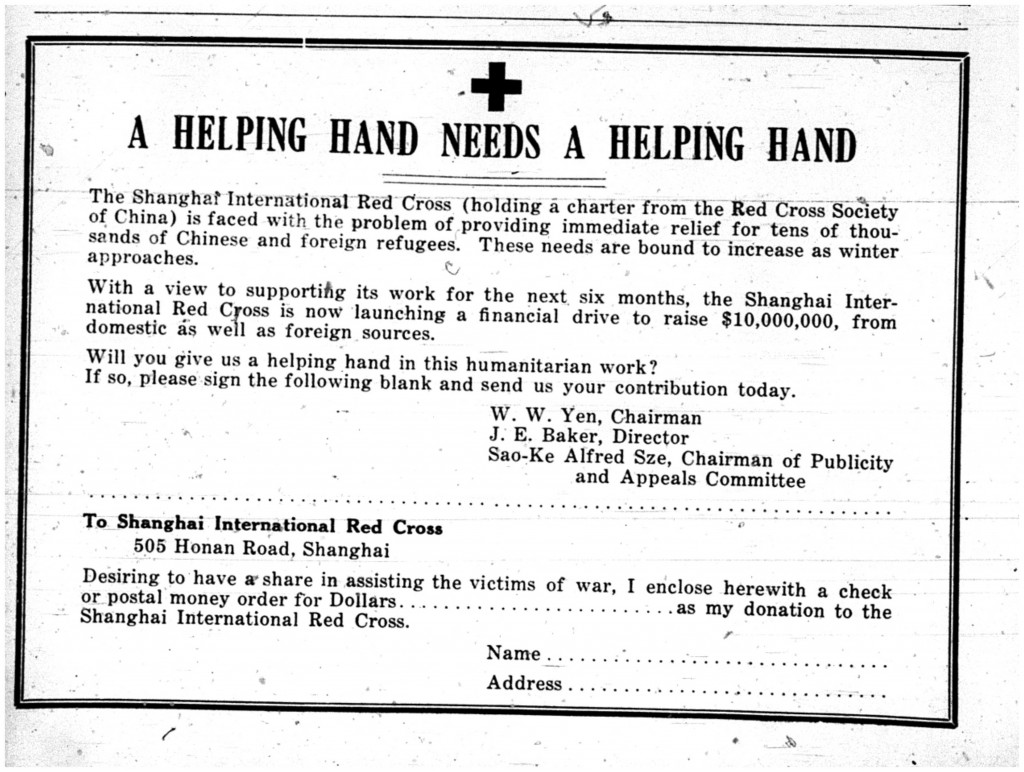

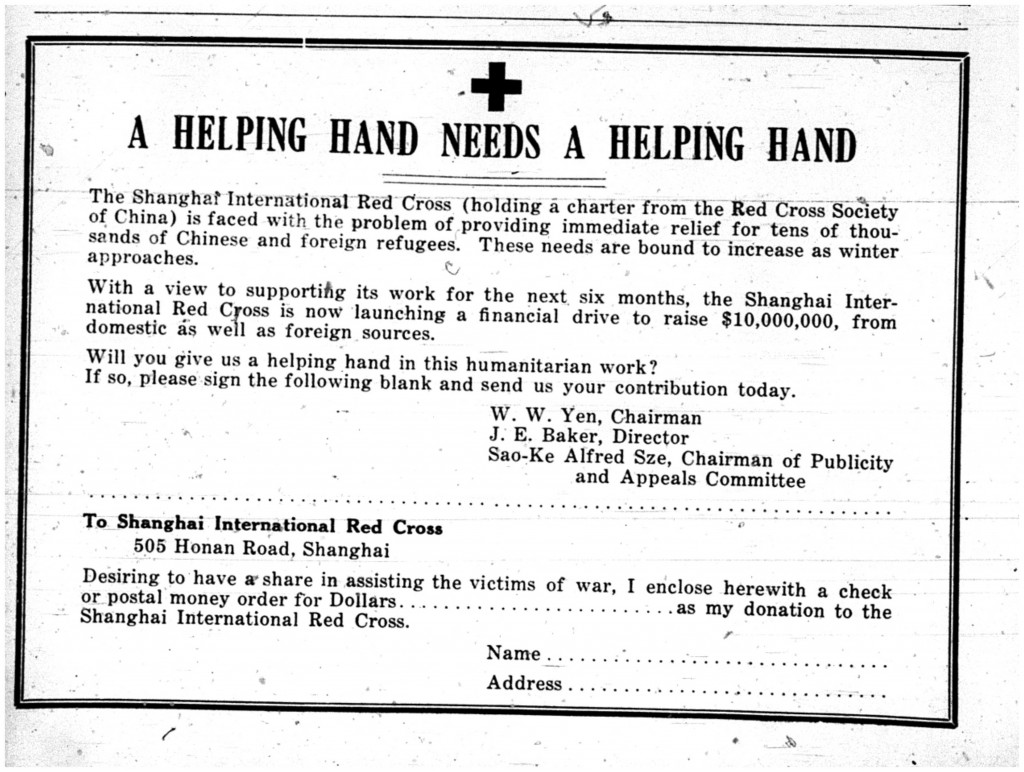

Nowadays in China The Red Cross and other major charities may look a bit dodgy – government controlled GONGOs seemingly full of self serving corrupt officials and secretaries with a love of using donations to buy LV bags.But the Red Cross has a long history in China and Shanghai – here’s an appeal for donations from around the late 1930s targeting Chinese and foreign refugees in Shanghai faced with the imminence of a very cold winter.

Posted: January 25th, 2012 | No Comments »

I’ve plugged the great Megan Abbott on this site before and her great Californian noir books. I just happened to be reading her novelisation of the 1931 LA Trunk Case Murders, Bury Me Deep. It’s a cracking read and well worth the effort. However, she has a throwaway line about someone having a top of the range “RCA Victor Electrola with swank Oriental trimmings” – well I had to know if such a wireless had ever existed. And it did – a Chinoiserie radio!!! Limited Edition too!! Here’s the details from an old wireless enthusiasts site:

RCA,GE and Westinghouse were in a partnership running Victor since early-1929. Actually two companies were formed to run Victor, (AudioVision Appliance and Radio-Victor.) In late 1929, RCA-Victor was formed to consolidate everything into one company. In 1930, an Anti-trust suit was filed against the group which broke-up the longtime partnership (cross-licensing arrangement) and essentially put RCA in sole ownership of RCA-Victor. Due to the Depression, expensive machines were no longer a saleable item, so RCA-Victor utilized left-over cabinets from the previous year’s most expensive model, the 9-56 Automatic Electrola-Radiola, ($1750 selling price in 1929) and replaced the 9-56’s problem prone Radiola 64 and notorious automatic changer with the reliable ten-tube Microsynchronous TRF receiver and a simple manual turntable. Standing 65″ tall, the Chinese Chippendale cabinet is decorated with oriental motifs in red, black and gold lacquer. Walnut veneer panels with black, gold and green lacquer trim are used on the exterior. With the doors closed, ten filigree bronze hinges and the filigree bronze door-pull escutcheons are visible. Selling for a mere $595, only 245 of these behemoths were produced.

You can keep your wanky iPods, I’ll have one of these please

You can keep your wanky iPods, I’ll have one of these please

Posted: January 24th, 2012 | 1 Comment »

Noting this book, Mission to China about Ricci, afraid I haven’t read it yet – blurb and cover as usual below:

In the sixteenth century, the vast and sophisticated empire of China lay almost entirely unknown to Western travellers. As global trade expanded, this land of reputedly boundless wealth, pale-faced women, and indecipherable tongues began to feed the fantasies of European merchants and adventurers. The Catholic Church, meanwhile, saw in this great people millions of souls who would be damned unless the Christian message could be brought to them. In this book, Mary Laven tells the extraordinary story of the first Jesuit mission to China. Confronting enormous challenges, the Italian priest Matteo Ricci and a tiny handful of learned companions gained permission from the notoriously xenophobic Wanli emperor to settle in the fabled Forbidden City. Living among eunuchs and mandarins, wearing the clothes of Confucian scholars, Ricci and his associates strove to master the language and culture of their hosts. At the same time, they energetically preached the virtues of Western art and science. In Mission to China Mary Laven brings this remote world vividly to life.

Mary Laven lectures in History at the University of Cambridge, and is a Fellow of Jesus College. She grew up in Canterbury, and apart from interludes in Venice and York, has spent most of her subsequent life in Cambridge. She loves Italy, archives, beer, and walking around the suburbs of unfamiliar cities. Her first book, Virgins of Venice: Enclosed Lives and Broken Vows in the Renaissance Convent, won the John Llewellyn Rhys prize.

Posted: January 24th, 2012 | No Comments »

Danwei (which now appears, after a long time in the commie dog house, to have been unblocked in China) has a history of Chinese serial killers by Robert Foyle Hunwick. He catalogues suspected and known serial killers in the PRC from the early 1980s the the present (the apparent rise of the serial killer being seemingly in a similar arc to the introduction of capitalism and the market to China may of course by mere coincidence and you can choose to believe that if you want!). It does seem that just as China scoops all the golds at the Olympics it’s serial killers are also off the scale in terms of their numbers – Yang Xinhai with 65 victims is thought to be China’s worst serial killer. Unsurprisingly perhaps prostitutes and sex workers seem to be the main targets of these men in many cases. Also the now transitory nature of much of Chinese society, migrant wanderers without any stable sense of community – indeed with all the displacement of traditional communities it seems all too easy to murder and walk away; the neighbours won’t check for ages! There are also big questions of police capabilities in these kinds of cases and to co-ordinate nationally as well as the media’s complicity in hushing up cases on occasion leading to the raft of rumours that fly around China constantly.

And if you want a China Rhyming theme (history doesn’t repeat itself but it does rhyme) then Foyle Hunwick refers to the spate of kidnappings now rampant, particularly in Shenzhen. Of course kidnapping was a criminal disease in the 1930s too, though mostly of the wealthy rather than children (and, again, should you wish to draw lessons from the one-child policy and forced social engineering from this then I won’t stop you!).

A fascinating article well worth a read.

Posted: January 23rd, 2012 | No Comments »

As it’s the Chinese New Year holiday a longer piece today as you might have some time to read. I persuaded friend of China Rhyming, Anne Witchard, author of the forthcoming book Lao She, London and China’s Literary Revolution (RAS Shanghai-Hong Kong University Press) to make a few notes from her recent reading on Noel Coward’s first encounters with China and his relationship with Jeffery Holmesdale, the fifth Earl Amherst, who’s esteemed ancestor had been British Ambassador to China and refused famously to kow-tow. It takes us from dope dens in Limehouse and Tallulah Bankhead to tramp steamers at Haiphong!!

In 1927 the society beauty, Lady Diana Cooper remarked: ‘Noel Coward is on the edge of a nervous breakdown which he proposes to have in China.’ Coward was 27 and already rich and famous. His first attempt at a Chinese nervous breakdown however would take him only as far as Honolulu where he was waylaid by the charms of La Pietra, a coral-pink Italianate villa nestled among cocoa palms and scarlet hibiscus. It belonged to Harold Acton’s aesthetically inclined cousin Louise, and was a paradisial place to plot up. However the lure of Far Eastern consolations was irresistible to Bright Young men of the Twenties and two years later it was announced in the New York Times (November 1929) that ‘Mr Coward is to embark on a trip round the world […] He will be joined in Japan by Jeffery Holmesdale, who used to write […] for the New York World, and together they will venture deep in Japan and China. Mr Coward may be gone for a long time.’

Coward had first met Jeffery Holmesdale, the future fifth Earl Amherst, in 1920 at a Park Lane party thrown by the pale and willowy Earl of Lathom. In the aftermath of war, a ‘corrupt coterie,’ as Diana Cooper described her set, hedonistic and stage-struck young aristocrats, artists and theatre people, became renowned for their lavishly decadent lifestyle. Amherst recalled ‘cocaine on the table’ in West End nightclubs and at Tallulah Bankhead’s parties in Chelsea, of which one of her friends complained ‘ I’m sick and tired of Talullah’s parties. Every morning they run out of cocaine, and it’s me whose sent down to Limehouse to get some more!’ In 1920 Amherst was about to resign his commission in the Coldstream Guards having served in the war and earned his Military Cross. Slightly built with blond hair and blue eyes he was the scion of an esteemed family. The 1st Earl Amherst was ambassador to China whose famous refusal to perform the ko-tou ceremony before the emperor gave kow tow to the English language. His forebear and namesake Sir Jeffrey Amherst had been commander-in-chief of the British Army during the American War of Independence, his reputation tarnished for supposedly endorsing the giving of blankets infected with smallpox to the Native Americans. Coward described Amherst as ‘gay and a trifle strained’ with ‘a certain quality of secrecy […] as though he knew too many things too closely.’ He was immediately attracted to this blond-haired aristocratic young officer whose air of mystery contributed to his appeal. That night they left the party together. ‘I watched him twinkling and giggling through several noisy theatrical parties’ Coward recalled later, ‘but it took a long while for even me to begin to know him.’ Soon after they met, in 1921, Amherst got a post as a journalist on New York World and seeking to establish his name on Broadway, Coward journeyed with his new friend on the luxurious Cunard liner Aquitainia – known as The Ship Beautiful. They stayed at the Algonquin Hotel and one of first things they did was to go sightseeing in Chinatown. During the years that followed, Coward made as sensational an impact on New York as he had in London. By 1929 he was ‘getting egg-bound, mentally that is’ as he informed Amherst, and suggested that he break from reporting gruesome crime stories and writing theatre reviews and join him on his trip to China.

Coward sailed from San Francisco on the President Garfield (29 November) once again stopping at La Pietra. This time he joined the Tenyo Maru for Yokohama. He arrived in a snowstorm and took a taxi to Tokyo which he described as a ‘sad scrap heap of a city’ sacrificed to Western aspirations. Here he waited three days for Amherst to join him for the start of a six-month adventure that would inspire some of his best known work, including the play Private Lives, which he conceived in the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright) while he was waiting for Amherst and would write up later in four days at Shanghai’s Cathay Hotel during a bout of flu.

The two friends with their twenty-seven pieces of luggage, including a portable gramophone, travelled from Nagasaki to Korea, then to Mukden where they attended a New Year’s fancy dress party with the British consul. Amid the amateur pierrots, now dusty images of the previous decade, Coward noted his countrymen’s isolation ‘condemned to stay in that grim, remote place perhaps for years.’ They journeyed on through northern China on a freezing train cocooned in a heap of fur coats, drinking vodka and repelling carriage invaders by cranking up Sophie Tucker’s Some of these Days to full volume on the gramophone.

As Coward recovered from his flu at the Cathay, the weather improved, and he enjoyed Shanghai, ‘a cross between Brussels and Huddersfield’ he wrote in a letter to his mother. They got to know three naval officers from HMS Suffolk moored on the Yangtse and soon they were dining riotously on board ship, and having a ‘fairly rowdy’ time. Coward persuaded the navy to let them travel on the ship to Hong Kong where propped up in bed in a dark blue flannel dressing gown, with notes scattered about and a portable typewriter he got Private Lives down on paper.

Back in Shanghai, they took a tramp steamer for Haiphong, sharing a cabin with a multitude of bedbugs and cockroaches, and were driven in a hired car along the coast to Saigon. The drive took a week and while jungles and rivers and mountains and rice fields were unrolling past the window of the car, Coward came up with a new song ‘Mad Dogs and Englishmen’. From Singapore they took a night train to Kuala Lumpur and visited Coward’s younger brother Erik who was stationed at a tea plantation near Colombo, Ceylon. On a P & O boat home from Ceylon to Marseilles they were asked to judge a fancy dress competition. When they awarded the prize to two pretty young Eurasian girls, ‘with much the best costumes’ the caste-conscious planters wives were annoyed. After Coward discovered that there wasn’t a mother among them whose daughter didn’t dance and sing he took his revenge with the song ‘Don’t Put Your Daughter on the Stage’. A lesser known product of the trip was a song ‘Half Caste Woman’ which Coward wrote for Charles B. Cochran’s 1931 Revue, from which it was cut after just a few weeks.

Drink a bit, laugh a bit’ love a little more

I can supply your need

Think a bit, chaff a bit, what’s it all for

That’s my Eurasian creed

The set design featured several flappers languorously decorating a whisky bar (Graham Hodges’s Anna May Wong). A song about prostitution was rather risky for the conservative attitudes of the 1930s but it was picked up by Anna May Wong who chose it as as her signature tune.

In later life Amherst remained reticent about his friendship with Noel Coward, speaking movingly of their attachment but declining to delve deeper, their relationship remains shadowy and essentially private.

Info from Philip Hoare Noel Coward: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. 1988

Also see Jeffery Amherst, Wandering Abroad. Secker and Warburg. 1976