Remembering the Start of the South China Morning Post in 1903

Posted: December 12th, 2015 | No Comments »As the South China Morning Post is now probably about to exit the market as a serious independent newspaper (mainland firm Alibaba having agreed on Friday to buy the media assets of the SCMP Group) it might be worth recalling its rather rocky start back in 1903…

From my book Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao….

The Arrival of the Post

At the same time, the press in Hong Kong was growing but it wasn’t exactly a boom time: by the early 1920s the combined circulation of English-language papers in the colony was barely 5,000 daily. The South China Morning Post was founded in 1903 and published its first edition in November, declaring itself the colony’s first “modern newspaperâ€. The press was also becoming a force for social progress in Hong Kong by making suggestions that influential citizens of the colony adopted. Hong Kong’s China Mail first proposed combining the existing medical and technical colleges to form a university for the colony, an idea the Parsi businessman Hormusjee Mody took up at the insistence of prominent businessman Paul Chater and bequeathed its major building to the new Hong Kong University. Unfortunately, Mody died before the university building was completed.

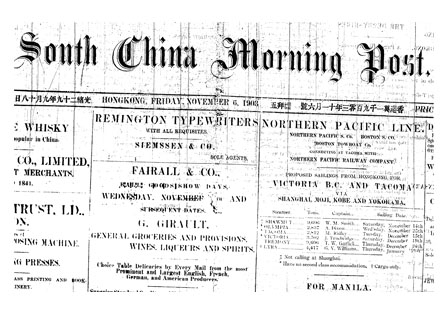

The South China Morning Post, or the Post as it quickly became commonly known by everyone, was to outlive its major competitors, the Hongkong Telegraph, the Hongkong Daily Press and the China Mail to become regarded as one of the best papers in the Far East. The Post’s launch wasn’t popular with the competition. As the Hongkong Telegraph noted, “Hongkong’s troubles are to be increased by the addition of a new daily newspaper with the voluminous title of The Morning Post of South China … We sympathise deeply with Hongkong. It will soon be as bad as Shanghai in this respectâ€. The paper’s founders —Arthur Cunningham who had covered the Sino-Japanese War for the Hongkong Daily Press in 1894 and the Australian-born Chinese political activist Tse Tsan-tai — begged to differ. The Post marked somewhat of a sea change in Hong Kong, declaring in its opening editorial on 6 November 1903:

The modern newspaper has taken the place of the old-time ambassador. The cynic has said the ambassador is sent abroad to lie for the good of his country. The newspaper is sent abroad to tell the truth for the good of humanity. Whereas the ambassador, by means of weary months of negotiation, may make or prevent a war; a newspaper by means of a few trenchant articles, so be that they have truth behind them, will rouse a public to resent aggression, so to reform abuses, to mould the policy of governments. Such is the power of the modern newspaper.

Tse Tsan-tai, who had been baptised James See, was a particularly transnational character for the times. Born in Grafton, Australia, to a family of Chinese merchants, he moved to Hong Kong in 1887 to study at Queen’s College and was one of the founders of the Literary Society for the Promotion of Benevolence (Furen Wenshe). In 1895 Tse and his colleagues aligned themselves with Sun Yat-sen’s Hing Chung Hui (Society for the Restoration of China), though Tse and Sun soon fell out. Tse recalled Sun as “… a rash and reckless fellow. He would risk his life to make a name for himself. Sun proposes things that are subject to condemnation — he thinks he is able to do anything — no obstructions — ‘all paper!’â€. Though history has crowded out Sun’s detractors

in the early days before he rose to power, there are many and his nickname was the “windbagâ€. Later, in the 1930s, a heated debate would arise in Australia when some prominent overseas Chinese campaigned to have Tse recognised as the true father of the Chinese Republic, thereby arguing for the demotion of Sun.

Tse pushed hard for social change in Hong Kong, arguing that the Chinese community should elect the Chinese representatives on the Legislative Council rather than having them nominated by the governor, as well as inventing an advanced steering system for airships. He campaigned against superstition, feng shui, footbinding and opium smoking, while promoting religious tolerance, railways and mining, and calling for the protection of China’s heritage. He had corresponded with Morrison since the 1890s, was friendly with the Hongkong Telegraph editor Chesney Duncan and also knew Cunningham well when he was the editor of the Hongkong Daily Press. In 1901 Tse worked briefly for the China Daily, the newspaper of the Society for the Restoration of China. As well as being a prolific journalist and newspaper proprietor, Tse also authored about half a dozen books on subjects ranging from ancient Turkestan to solving unemployment, to why typhoons occur. He was nothing if not a multi-tasker.

Tse and Cunningham appointed Douglas Story as the paper’s first editor. Their founding aim was to present the viewpoint of both the British colonial regime and the business community and promote the cause of republicanism in China. This was a tricky project and wasn’t an easy balancing act. Story only lasted a year, claiming that he didn’t like Hong Kong because people took too many holidays and played too much sport. However, he was a staunch supporter of self-government for Hong Kong and considered the governor’s post unnecessary. Transition from a crown colony to a self-governing colony would allow Hong Kong to flourish and also allow for greater Chinese involvement in affairs. Although in a seeming contradiction to opposing crown colony status, he also staunchly defended the rights of British trade in China and spoke out against what he saw as American encroachment on British business interests — Washington’s “Open Door†policy.

Despite all this, the Post’s early survival was far from sure. Within a few years at the turn of the century several new papers, as well as the Post, appeared in Hong Kong along with the nearby Canton Daily News, which sought to compete with the rather larger and well-established Canton Chronicle. It seemed that, although the market was already crowded, investors thought newspapers were a potentially profitable investment, but this wasn’t initially the case. Despite the rather vague claims from the backers of the Post that investments in the paper would earn returns of anywhere between 12% and 200% a year when they issued $150,000 worth of shares at $25 each, three years later shareholders had received no dividends and the shares were valued at just $18. The Hongkong Telegraph gloated over the Post’s initial financial woes, noting both the difficulty of the English- language newspaper business in Asia and remembering the early days in the Canton factories: “Conditions in the Far East have changed since the time when anybody could come along with a hand press and start a paper …â€. Despite this gloomy prognosis, the Post persisted and ultimately outlasted all the competition.

The Post survived its early traumas. Various acting editors ran the paper until 1910 when Angus Hamilton was appointed, but he lasted only a few months. Hamilton, an English correspondent of aristocratic background, had started out working on the New York Evening Sun which sent him to Korea. He then found work as a war correspondent for the Times, covering the defence of Mafeking alongside Baden Powell before moving to the Pall Mall Gazette where he covered the Siege of the Legations, the wars in Somaliland and those between the Balkans and Macedonia at the turn of the century. Then, job-hopping again, the Manchester Guardian hired him to report from the frontlines during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, and he also visited Afghanistan before finally being hired by the Post. Though an immensely talented man, he was also troubled and restless. He lingered in Hong Kong for only a short while before heading to India and then becoming a reporter for Britain’s Central News Agency in the Balkans where he was twice captured by the Bulgarians and severely tortured as a Turkish spy. He travelled to America to give a series of lectures on his experiences around the world, only to discover he was a poor speaker, nervous and attracting small audiences. Considering himself a failure, in dire financial straits, suffering from ill-health courtesy of his Bulgarian torturers and unsure of the future, he cut his throat in a New York hotel room.

As the immediate terror of the Boxers receded, China found itself faced with new challenges — a continually ossifying Qing court that had caused the humiliation of China, as a result of which the country had to accept a greater foreign presence on Chinese soil. At the same time, other rising powers chose China as a battlefield for their grievances.

Leave a Reply